Despite offering “more than 280” works of art while putting on display many pieces that haven’t been seen in decades, the Museum of Fine Arts’ current “Degas to Picasso” is no blockbuster, and it doesn’t pretend to be. Drawn from the MFA’s holdings, and snaking from the Torf Gallery out into the Lower Rotunda and then into the Trustman Gallery, it limns the development of modern art in Europe, from 1900 to the 1960s, starting with Degas’s Dancers in Rose and culminating in Picasso’s The Rape of the Sabine Women. Cézanne is absent, but Picasso is ubiquitous, and the supporting cast includes Léger, Matisse, Rouault, Gris, Miró, Calder, Man Ray, Munch, Klimt, Klee, Schiele, Nolde, Kollwitz, and Beckmann. There’s no catalogue, so you focus on what appeals to you and write your own art history.

Despite offering “more than 280” works of art while putting on display many pieces that haven’t been seen in decades, the Museum of Fine Arts’ current “Degas to Picasso” is no blockbuster, and it doesn’t pretend to be. Drawn from the MFA’s holdings, and snaking from the Torf Gallery out into the Lower Rotunda and then into the Trustman Gallery, it limns the development of modern art in Europe, from 1900 to the 1960s, starting with Degas’s Dancers in Rose and culminating in Picasso’s The Rape of the Sabine Women. Cézanne is absent, but Picasso is ubiquitous, and the supporting cast includes Léger, Matisse, Rouault, Gris, Miró, Calder, Man Ray, Munch, Klimt, Klee, Schiele, Nolde, Kollwitz, and Beckmann. There’s no catalogue, so you focus on what appeals to you and write your own art history.

The first thing you see on entering the Torf Gallery is Dancers in Rose. Degas drenches the conservative subject matter — four ballet dancers seen from the rear, one partly obscured — in a shimmering haze that oscillates between rose and blue. Their arms are raised in congruent port de bras; it’s about community, not identity, four woman who are not stars and likely never will be but have now been immortalized in art. Degas locates the fulcrum between classic and modern, stasis and movement, Euclid and Einstein — you can practically see his forms vibrating between particle and wave.

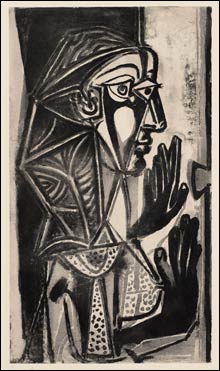

But just as the fizz goes out of the MFA’s concurrent “Facets of Cubism” after the initial Champagne burst, so the rose-and-blue of “Degas to Picasso” becomes mostly blue. All art is in a constant state of tension with reality, and painting from Corot to early Cubism was in a constant state of tension with photographic reality, Manet, Monet, Seurat, Van Gogh, Cézanne, Picasso and the rest seeking to redefine the language of art, the language of seeing. In the 20th century, the vocabulary of art breaks down and the explorers lose their base: artists do more and more, but it means less and less. Picasso is the 20th century’s signature artist: fluent in every language and prolific in every genre, and yet as his career progresses through Blue and Rose Periods and then Cubism, he no longer has anything to say. Woman at the Window (1952) is all radical chic, more conservative and less modern than Caspar David Friedrich’s 1822 painting of the same title. The Rape of the Sabine Women recycles a style and a political sensibility that Guernica had birthed and exhausted.

The most challenging pieces in “Degas to Picasso” are the ones that look back. The seven figures of Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta’s massive My Uncle Daniel and His Family (1910) — which include a dog and three flirtatious young ladies — dwarf the quivering, Van Gogh–turbulent landscape behind and beneath; dressed all in black, they’re the Basque descendants of Piero della Francesca subjects. Raoul Dufy’s two 1910 woodcuts, Love and Fishing, conjure mediæval Cubism in their frontal presentation. Lyonel Feininger’s Regler Church, Erfurt (1930) translates Cézanne’s planes of earth and stone into planes of air and light.

The most modern entry could have been painted in a monastery. Giorgio Morandi’s Still Life of Bottles and Pitcher (1946), six bottles and a pitcher, all in his trademark palette of cream, beige, gray, ocher, and steel blue, huddle together against a similarly muted background. Too simple to be disturbing, you think, and yet it is. Where does one shape leave off and another begin? Where does the light come from? Morandi keeps raising the uncomfortable questions most of his modernist peers had stopped asking.

ADVERTISEMENT

|

Real modern art arose in the 15th century, at the dawn of Renaissance humanism, when artists began to paint what they saw rather than what they knew. “I call a sign,” Leon Battista Alberti wrote in his treatise De pictura, “anything that exists on a surface so that it is visible to the eye.” But to a Dominican friar like Giovanni da Fiesole (circa 1395–1455), whom we know as the artist Fra Angelico, a sign was an operation. To Alberti, a figure in an Annunciation was the angel Gabriel or the Virgin Mary; to Fra Angelico, the figure in any Annunciation was the relationship between the two. Alberti’s isn’t just a different way of painting, it’s a different way of living. Next to that revolution, the one we call modern art is just a surface phenomenon.