Expect no flash from Stephen Fisher, no canvases of dead insects, no frontal nudity, no puns, no effort to exaggerate, shock, disarm, or confront. Don’t even expect color. Expect instead something so simple and pared down that once you start looking you’ll have a hard time stopping. Fisher draws what (I presume) he sees, and what he chooses to look at — bell jars and hourglasses, globes and darts, fans and compasses — grows interesting not just because he gracefully crowds his varied, meticulously rendered objects onto whistle-clean table tops (they’re like shrines of what’s just come down from the attic) but because the objects themselves make us think about the magic of seeing.

Expect no flash from Stephen Fisher, no canvases of dead insects, no frontal nudity, no puns, no effort to exaggerate, shock, disarm, or confront. Don’t even expect color. Expect instead something so simple and pared down that once you start looking you’ll have a hard time stopping. Fisher draws what (I presume) he sees, and what he chooses to look at — bell jars and hourglasses, globes and darts, fans and compasses — grows interesting not just because he gracefully crowds his varied, meticulously rendered objects onto whistle-clean table tops (they’re like shrines of what’s just come down from the attic) but because the objects themselves make us think about the magic of seeing.

We tend to think of magic as the manifestation of the impossible: the disappearing coin, the disembodied lady, the rabbit that materializes from a top hat. But maybe magic lives much closer to the real world; maybe it’s the dramatization of what we experience every day. Who doesn’t know that fortune is fickle? Who among us don’t leave our bodies behind each night when we sleep? Who hasn’t been startled by a creature that appears out of nowhere?

Stephen Fisher’s form of legerdemain involves placing apparently random objects together on a reflective surface. In all three of his drawings in the intelligent and gratifying exhibit at the Pepper Gallery, that same tiled table top is positioned beside a window. Through the open slats of the window’s venetian blind, horizontal stripes of light ripple on the table’s surface, which itself is making a double of everything it holds. The result is a circus act of shadow and light and refraction. The light also catches and bends in the other reflective surfaces that make up Fisher’s stately, dust-free clutter — the eyeglasses and magnifying lenses, the candy tin and the wind-up toy. Everything is a mirror of everything else, still lifes in which all comes alive in the orchestrated play of light.

The randomness of the objects Fisher draws is actually more sleight of hand. There isn’t an artifact in these frames that couldn’t have been around a century ago: the miniature dirigible, the jumping jacks, the wire-rimmed spectacles, the wooden dart, the glass marble, the map on the globe that balances on its tooled oak pedestal. These pictures suggest a kind of high seriousness (not just for their photographic precision but also for the less identifiable objects that look as if they’d come from an old science lab), but they’re in fact things you’d expect a kid to collect. And not just any kid. The objects of Fisher’s world are either instruments for scientific investigation or toys. The juxtaposition is sobering and even painful: science and play both delight in the imagination, and yet everything we see no longer exists. Gone is the world of these antique wind-up toys, home experiments, uncovered electrical fans. But not entirely. The child who collected these treasures is now the artist who celebrates them in all their light-dappled, thrilling ephemerality.

Michael David is every bit as much a craftsman; but he’s far more sensual. The first time I saw a Michael David drawing was years ago at an overcrowded “Drawing Show” at the Boston Center for the Arts. Wedged among hundreds of competing images, his piece quietly stood out for its extraordinary technique and its sensual presence. Vertical gray drips (possibly graphite or watercolor) at first appeared to be pure abstraction. Then, slowly, the subject matter emerged: the shadow of a body seen behind the spray of a shower stall. The one Michael David exhibit I’ve seen since featured green, interlocking networks of grasses and leaves.

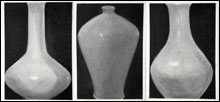

It’s clear he’s attracted to repetitive patterns that in their aggregate become something larger and resonant, and he’s achieved that again in his 2005 Vase Suite. Light reflects off each of these 21-by-14-inch body-like forms in a way more suggestive of a museum case than sunlight: shadowless, they glow with an even luminosity, earthen jewels. The centerpiece of the triptych is both the darkest of the three vessels and the only one that swells to a wide upper region and a small, squat neck. The two flanking it are more like decanters you’d find on a ship: wide at the base and with long, thick necks, they’re less about flowers than about water or wine.

It’s clear he’s attracted to repetitive patterns that in their aggregate become something larger and resonant, and he’s achieved that again in his 2005 Vase Suite. Light reflects off each of these 21-by-14-inch body-like forms in a way more suggestive of a museum case than sunlight: shadowless, they glow with an even luminosity, earthen jewels. The centerpiece of the triptych is both the darkest of the three vessels and the only one that swells to a wide upper region and a small, squat neck. The two flanking it are more like decanters you’d find on a ship: wide at the base and with long, thick necks, they’re less about flowers than about water or wine.

One of the most interesting and subtle aspects of the vases is how each of them has been cropped. You’d think that in these full, frontal studies of texture and form we’d get to see each vase in its entirety, but that view is withheld. Rather, the bases disappear into the bottom of the frame, and the two outermost vases are also cropped at the top so that the horizontal moment where you expect to see the lip turn inward remains barely but permanently out of view. All three stand slightly off center to the left, a point emphasized by the left vase’s edging out of the frame.