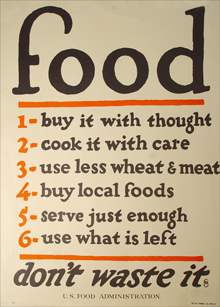

Imagine if we put by all the words we put up. What would the future make of the notice you just hung for the sake of your significant other’s punkabilly band, your lost mongrel, or your Pissed-Off-Voter ennui? At once art and artifacts, nothing beats posters for a view of history’s daily doings, hankerings, and disputes. Curious about what generations of Mainers have been hanging up over the years? They’ve barked the merits of stud services and midget expositions, the convictions of teetotalers and of flatlanders, and the Maine Historical Society has put ’em up in their current exhibit: A Riot of Words, a fascinating collection of printed posters ranging from early 18th century broadsides to World War I era color lithographs.

Imagine if we put by all the words we put up. What would the future make of the notice you just hung for the sake of your significant other’s punkabilly band, your lost mongrel, or your Pissed-Off-Voter ennui? At once art and artifacts, nothing beats posters for a view of history’s daily doings, hankerings, and disputes. Curious about what generations of Mainers have been hanging up over the years? They’ve barked the merits of stud services and midget expositions, the convictions of teetotalers and of flatlanders, and the Maine Historical Society has put ’em up in their current exhibit: A Riot of Words, a fascinating collection of printed posters ranging from early 18th century broadsides to World War I era color lithographs.

If you’ve ever put up a halfway artistic flyer, you’ve probably imitated the “classic broadside” style, with its ornate and wildly varied fonts, its fun borders, and its gratuitous exclamation points. But like it’s taking us a while to get a handle on how best to use the Internet, it took printers a while to come around to an inviting visual style. One of the oldest documents on exhibit, a 1738 broadside that recognized the incorporation of Brunswick, is dense with ink and a small, serif-y typeface. Compare it to the box-of-chocolates graphic whimsy of a 1860 playbill for a traveling show at Deering Hall: The flyer trumpets the name of the troupe-leader, “HERNANDEZ,” in white caps, intricately decorated with scrolls and trefoils. And “THE GREAT MORESTE” — in black caps with white outline — is advertised to have wonderful skills on the “HORIZONTAL BAR!,” which is freckled with circus-like dots and bouncy, baubly serifs. Very beguiling.

More somber but equally provocative are the black coffins that top many earlier 19th century broadsides. Then as now, news and entertainment tended toward sensationalistic commingling, and ballads relating the most current untimely ends were commonly sold in the streets for a few cents. The 1811 hanging of Ebenezer Ball, for murder, was morbidly commemorated by dramatic pre- and post-execution verse, and printed on a broadside along with a stark cut of a hanged man dangling from the scaffolding.

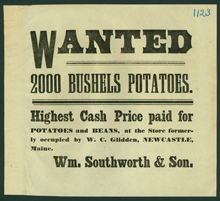

As the century wore on, improved literacy rates turned more people to newspapers for news, and with paper and fonts growing cheaper and more widely available, broadsides became a showy realm of promotion for the everyman. “YOUNG MAC!!!” exults the header of one flier, in bold caps as tall and sinewy as the legs of the stallion it advertises. Just below is a wood-cut illustration of the black horse, looking dashing but modest, whose services — euphemistically hawked as “the improvement of stock” — are so aggressively available. The advertisement is one of many on exhibit, typical of a growing mid-19th century middle with money to spend, commerce to conduct, and clever new inventions to peddle (look for the “Zylanite” false shirt-front inserts, meant to fool people into thinking you laundered regularly).

As the century wore on, improved literacy rates turned more people to newspapers for news, and with paper and fonts growing cheaper and more widely available, broadsides became a showy realm of promotion for the everyman. “YOUNG MAC!!!” exults the header of one flier, in bold caps as tall and sinewy as the legs of the stallion it advertises. Just below is a wood-cut illustration of the black horse, looking dashing but modest, whose services — euphemistically hawked as “the improvement of stock” — are so aggressively available. The advertisement is one of many on exhibit, typical of a growing mid-19th century middle with money to spend, commerce to conduct, and clever new inventions to peddle (look for the “Zylanite” false shirt-front inserts, meant to fool people into thinking you laundered regularly).

Of all the commerce under way among the middle of the era, none was so contentious as the liquor trade, and the growing temperance movement spawned some of the most inspired public treatises on the morality debate. Posters on display present a large wood-cut of a young drunk sprawled outside a tavern, a bold public denouncement of the “Liquor Power in Politics,” and the true ballad of a mad-as-hell wife causing a ruckus at Harry Cole’s Rum Saloon.

John Mayer’s curation of A Riot is thorough and visually rich, with multiple copies of the old broadsides posted up on planks to conjure up the texture of a well-papered 19th century Portland. Although a stronger sense of chronology in the broadsides’ arrangement might have helped reveal the medium’s graphic evolution, this exhibit is smart, accessible, and delightfully hands-on. In addition to printed matter, the exhibit also includes a letter press, circa 1820, a set of big wood type, and a table-top roller press with which visitors may get inky themselves.

Anyone who regularly hoofs it around Portland knows that the flyer is far from dead, and A Riot includes an affectionate homage to the modern legacy of the broadside: the Xerox. In a corner of the exhibit, shrine-like, are posted a smattering of notices for SPACE shows, LPOV meetings, and other cultural events of our fair city. It’s a nice touch, cozy and populist, and it really makes you stop and relish print’s sweet promiscuity. With reverence, affection, and wit, A Riot of Words celebrates the history and means of how we get our words around, and raise them up.

A Riot of Words: Broadsides and Ballads, Posters and Proclamations |

Maine Historical Society, 489 Congress St, Portland | Curated by John Mayer | Through June 11 | 207.774.1822

On the Web

Maine Historical Society: www.mainehistory.org

Email the author

Megan Grumbling: mgrumbling@hotmail.com