|

Last summer, Los AngelesTimes dance critic Lewis Segal suggested that ballet is dying an ugly, boring death. As always with this sort of thing, sides were taken, battle lines were drawn, letters and counterpoint articles were written. The take-home, however, shouldn’t be that in these times of iPhones and astro-diapers the tale of a half-swan/half-woman can’t be relevant — if that were true, we’d be throwing La bohème, Hamlet, and Great Expectations out the window as well. And yet, there is a problem with ballet these days: too many companies presenting mediocre dances and dancers.

Which is why the US debut at Jacob’s Pillow of the Swiss company Ballet du Grand Théâtre de Genève was such an unexpected gift. Neither of the two pieces BGTG performed, Japanese choreographer Saburo Teshigawara’s Para-Dice and Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Loin, was classical, and I did hear one woman in the parking lot complain that when a company has the word “ballet” in its title, there should be ballet. But symphony orchestras present new compositions alongside centuries-old works, and ballet companies have to do the same.

BGTG comprises a broad range of ethnicities and heights — no cookie-cutter corps de ballet here — and yet this is true ensemble dancing. Para-Dice is a paean to air — its currents in the world as well as the breath inside us — and the eight dancers project this most abstract of concepts. The women’s swooping undulations in their backs seem a soft antithesis to the sharp contractions of Martha Graham. The exploration of air became an exploration of space, and then, perhaps inevitably, of time. Ferried by the now pulsating, now ambient “sound creation” of Willi Bopp, the men cut through space with vigor and purpose, or the dancers lie down one by one. Women walk forward, as if in a trance, then fall into the arms of the men, who fluidly pull them backward. The sequence is repeated again and again, and it looks deliriously addictive, like a dream you don’t want to wake from.

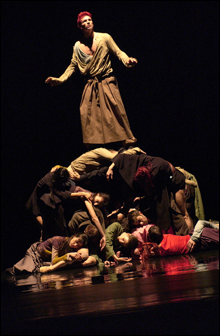

Loin was equally mesmerizing. The long, straight line that the dancers keep returning to hardly seems an interesting motif, but Cherkaoui more than compensates by having the dancers intone or mime hilarious tales involving the difficulties of touring (complete with the “monster” cockroaches who shared stages with them) or by moving the dancers through a polite ballroom dance of intertwining arms and foreheads resting against one another. The comedy of the stories does nothing to prepare one for the all-out dance phrases. The dancers are up, and then they’re down, with nary a sound. The sheer inventiveness of how they get there — now in quicksilver sweeps to the knee, now through the back by way of a shoulder — feels like a quick lesson in dance evolution, from folk dance to hip-hop. Whereas in Para-Dice the dancers are carried by air currents, in Loin, the unceasing sweep is of the tides.