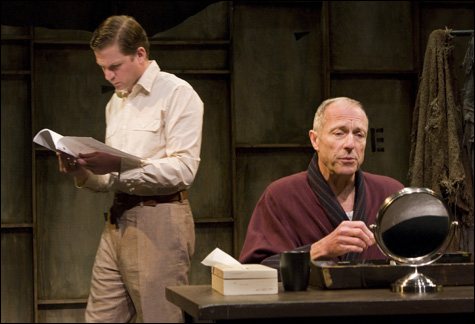

EXITS AND ENTRANCES: Will Lyman (right, with Ross MacDonald) proves he's more than just a pretty voice — not that he needed to. |

There are some playwrights whose work makes you think that a night at the theater is going to be an eat-your-vegetables affair — Arthur Miller, Henrik Ibsen, and South African Athol Fugard are often considered more vegan than visceral. But then you see a sharp production of one of their plays and you realize the menu is meatier than you had remembered, with payoffs as emotional as they are intellectual.

That's the case with Fugard's two-man 2004 play Exits and Entrances, which, directed by Chris Jorie at the New Repertory Theatre (through March 15), features a gem of a performance by Will Lyman as an aging actor confronting the dimming of his professional light. It's the perfect part to allow Lyman to prove he's not just a pretty voice. (He's the narrator of Frontline, Little Children, and BMW commercials.) Although if you've seen him in his increasingly frequent stage appearances around town — The Wrestling Patient at SpeakEasy is next — you don't need further proof.

Here he gets to show his chops in a play about everything from the purpose of art to aging and apartheid. For good measure, he acts out lengthy excerpts from Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, and Bridget Boland's The Prisoner, which is about the detention and show trial of Cardinal József Mindszenty in post-war Hungary.

It's in that last role that Lyman's character, the South African actor André Huguenet, adds what was seen to be the missing link in his previous performances — humility. Or at least, so says the play's other character, who's identified only as — drumroll, please — the Playwright.

The Playwright is, on some level, a stand-in for Fugard. Exits and Entrances is set between 1956 and 1961, when both the Playwright and Fugard were young, unsuccessful playwrights who found their voices after the Sharpeville Massacre, as they began to chronicle the evils of apartheid. The Playwright is also the Narrator (in a solid performance by Ross MacDonald), who tells us straight away that André is no longer with us and flashes back to two incidents in their lives.

It's easy to see Fugard in the Playwright, who limns André's tragedy as his inability to make meaningful contact with others as well as his inability to see a link between theater and the politics of the day. And if that's all there were to Exits and Entrances, it wouldn't be much of a play. But Fugard's particular talent has always been to transcend the limitations of political theater, to bring a Beckett-like sense of life's desperate moments to the table. There's more than a passing resemblance between Fugard's Boesman and Lena and Beckett's Vladimir and Estragon.

Here the Playwright is not a terribly interesting fellow. Fugard has to throw in a psychodrama with the writer's father in order to find any dramatic spark in him. Not only does André get the best lines, but Fugard also gives you the sense that he himself has quite a bit in common with the actor. There's the idea that new theatrical styles have left Fugard in the cold and the feeling, expressed in Valley Song, that he's now irrelevant to how South Africa develops.

And then there's the going, gently or not, into the good night. Toward the end, Lyman's understated recitation of "To be or not to be" has as many echoes of Beckett's contemplation of meaningless as it does of Shakespeare's almost existential call to action.

Throughout the 90 minutes, Fugard makes subtle connections between the Sophoclean and Shakespearean themes in André's performances and his own personal history. It never seems as if he were showing off, however. His playfulness with the language also keeps didacticism at bay. Like André, Fugard has learned to do less with more.

THE RANDOM CARUSO: This one has the charismatic Robert Pemberton as the sleazeball actor and not much else. |

The question about Fugard has always been whether his relevance would survive the end of apartheid. The question about Spalding Gray has become whether his work will survive the tragedy of his suicide in 2004.

Thanks to his widow, Kathleen Russo, the answer is a resounding yes. Russo — we know her as Kathie from his last few monologues — brought the Off Broadway hit Spalding Gray: Stories Left To Tell to the Institute of Contemporary Art last week with a quartet of like-minded authors and actors who at each performance were joined by a guest reader. Russo conceived the show; Lucy Sexton directed it.

Gray had been in the first rank of theatrical writers at the turn of the millennium. He was often called self-absorbed; some even blamed his suicide on that inability to get out of himself. But it was really his quest to go so far within himself that yielded the insights into sex and drugs, independence and fatherhood, and ultimately life and death, that made him such a great writer and that made his almost annual visits to Boston and Cambridge a must.