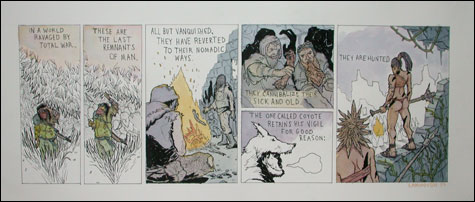

NOT QUITE FUNNY But still enlightening: A Ryan LaMunyon strip. |

The sad ghost of post-modernism. By Ken Greenleaf.

"THE FUNNIES" at Whitney Art Works, 492 Congress St, Portland | works by Ben Asselin, Jeff Badger, Nick Colen, Jay Cornell, Pat Corrigan, Amanda Curreri, Haig Demarjian, Sean Foley, Mike Gorman, Sam Henderson, Charlie Hewitt, Graham Kahler, Victor Kerlow, David Kish, Ryan LaMunyon, Amy Morken, Michael Nakoneczny, Deb Randall, Alex Rheault, Irene Stapleford, Tyler Stiene, Aaron Tompkins, Chad Verrill, Ty Williams, and Henry Wolyniec | through February 28 | 207.774.7011 |

"The Funnies" at Whitney Art Works is a sprawling show of upwards of 150 pieces by 25 artists, all of whom have been brought together by local artist — and show participant — Jeff Badger to make a point about cartoons, or perhaps several points. By "cartoons," we mean here work that comes under the broad heading of the comics as they might appear in that section of a newspaper.Not that most of these works would necessarily be in a publication, but they mostly all use something like that method making a piece of graphic art. Many of these pieces aren't funny or intended to be, but that's true of much comic art. "Comic" in this sense refers to a graphic genre, not to comedy. The unspoken assumption here is that the genre is an uppity response being held up as a mirror to the idea that there is other art that inherently possesses a higher level of accomplishment.

Comics have been around, of course, for years, and some of them have been very deep indeed. With his Krazy Kat strip in the 1920s and '30s, George Herriman sometimes produced wonderful surrealist visual and verbal poetry. In our own time Art Spiegelman's Maus addressed a difficult subject, the Holocaust, in surprising ways. Ben Katchor's Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer combines great drawing with lonely pathos and rewards re-reading.

Roy Lichtenstein referred to comics in his earlier Pop paintings, but he brought a highly trained visual intelligence to his work. Likewise, when Philip Guston went from abstraction to his more cartoon-like images, he still brought years of experience to them. In hindsight, neither artist looks as subversive as they first did. They were both really good painters.

The distinction between art with a commitment to seriousness and comic art is comprehension. It takes repeated visits to Matisse's masterpiece "The Red Studio" to learn to apprehend the deep aesthetic experience it provides. The same is true for Rembrandt, Cézanne, Caravaggio, or, for that matter, Beethoven. Great art takes time, attention, and patience. Cartoons are intended for quick amusement and the presentation of an easy-to-get idea.

But there is no continuum along which comics are placed lower than serious art — they are separate intellectual domains. There's occasional overlap, but the intentions and value are of each essentially distinct. Most of the pieces in this show make their point unambiguously. The idea might be indirect or cryptic, but it's right on top.

Take, for instance, Badger's own "Sell Me Your Eyes, I Need Them," in which the title appears in the painting, as do a metal head and a hand clutching money. While the circumstances implied are a little obscure, the message of imperative exploitation is sledgehammer clear.

There is one (at least) artist here who makes cartoons for publication: David Kish, who does Hoopleville for the Portland Phoenix. Here he shows 15 four-panel strips recounting the interaction between two children, Ahmed, who is Muslim, and Sarah, who is Jewish. It's called "Ahmed and Sarah, Friends Forever." They are mostly friendly, but Sarah does get anxious when Ahmed tries to show her his little rocket.

The ever-dependable Charlie Hewitt shows a couple of brightly colored sculptures that have some cartoon-like elements, but they are passing references in works that are, resplendent in their garish color, quite formal.

A couple of pieces by Henry Wolyniec, "Page 42" and "Page 25," are apparently fragments from a larger work. The framed works contain a number of small drawings that are, apparently, a narrative, and have, apparently, a larger context. I suspect Wolyniec's choice to show these works out of their context means that there is no context, and the viewer is expected to supply one. Wolyniec, who is usually as direct as a no-parking sign, is not above a little occasional misdirection.

In the first strip of Ryan LaMunyon's two multi-panel pieces, a group of desperate, cannibalistic men huddle together in a cold post-apocalyptic world, watched by scantily clad women. In the second strip the women are attacking from above, wielding sharp weapons and causing considerable gore. LaMunyon has a fine descriptive hand and a lively sense of action, but a war-ravaged future is a long-established staple of science fiction and graphic novels. In this world the men have no food but do have ammo for their AKs.