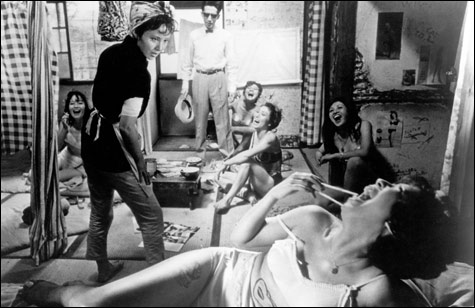

PIGS AND BATTLESHIPS: A battle between pigs for whatever slop there is. |

| “Vanishing Points: The Films of Shohei Imamura” | Harvard Film Archive: December 1-14 |

You can draw the time line of the Japanese new wave in scores of different ways — there were multiple possible launching points, and the big players evident in the ’50s and ’60s were young, old, and in between — but Shohei Imamura was an unarguably major, and quizzically ambiguous, figure in the landscape, an artiste among pulp mavens and a pop comic amid tragedians, a deep-dish cynic and a folksy absurdist. Dead last year at 79, the two-time Palme d’Or winner was one of the last of his slowly dying breed, survived still only by Seijun Suzuki, Kon Ichikawa, and Nagisa Oshima.He may have also been the least categorizable filmmaker of the lot (always a handicap in an auteurist world), careless with genre and frenzied about social critique. At the same time, it would be difficult to mistake an Imamura film for anyone else’s — few filmmakers ever had a more dire view of mankind. His was rooted to the verities of Japanese life in extremis. His characters are rarely more than a few stealthy crawl paces away from homicidal jungle law and pig-sty madness. The son of a doctor, he began as a studio apprentice with Yasujiro Ozu, and he quickly established a distaste for his sensei’s restraint and quiet eloquence. (Even Imamura’s interior spaces — always an æsthetic priority in Japan — are deliberately cramped and chaotic, in direct contrast to Ozu’s famous, measured rooms.) In fact, he has always seemed a sort of Japanese Sam Fuller, fascinated with working-class ruin and primal impulse. And he could be viciously funny — which alone set him apart from most of his industry’s big guns. His first phase, beginning in 1958, was taken up with racy comedies and melodramas, but it wasn’t till PIGS AND BATTLESHIPS (1961; December 8 at 7 pm) that he became, immediately, an internationally known voice. A defining self-portrait of Japan in the post-war moment, the film visits a virtual war zone of threadbare urban iniquity, a Japanese coastal city in which everyone is either a whore or a pimp, where emergent gangs kill each other over the right to control the black market in US Army food scraps, where capitalism isn’t even predation or victimization but a battle between pigs for whatever slop there is. It’s a cruelly comic movie (with a gangster’s corpse that keeps needing to be redisposed of), for the most part, because of Imamura’s domineering, amused disdain for his subjects — here was Japan’s incarnation of Buñuel, omnisciently satiric and utterly cynical, if not as graceful and subtle, and lasering through the Buñuelian derision for hypocrisy (religious, social, sexual, etc.) to hit the raw bone of untempered lust and hunger.

His style got looser and more modernist with the years, but Imamura’s world reflected his childhood experiences — he knew that with starvation and humiliation as primal forces, anyone can be driven to do virtually anything. THE INSECT WOMAN (1963; December 8 at 9:15 pm), a merciless tale about one raped woman’s helpless descent into whoredom, pimphood, and destitution that dares to limn more than 40 years of Japanese history in the process, and THE PORNOGRAPHERS (1966; December 3 at 7 pm) consolidated his position and sensationalized his career worldwide, as well as offering up a vision of modern Japan — as a rat pit of feral opportunism, debasing Americanization, and sex-industry violence — we hadn’t seen before, and one that became instantly de rigueur. (Suzuki and Yasuzo Masumura both took the baton and ran.) Contemporary Japanese culture had traditionally wrestled with honor in one way or another, but nobility and its stress rarely occupied Imamura; for him, the instinct and depravity underneath the social cheesecloth provided enough drama.

Neither did he frequently seek shelter in the period drama, another of his countrymen’s habits. As thoroughly crazy as it is, the nearly three-hour THE PROFOUND DESIRE OF THE GODS (1968; December 2 at 3 pm) is a kind of crystallization of Imamura’s ideas, transported to the purified landscape of an island so secluded its inhabitants have evolved into animistic, incestuous nuts. (Cut-off island communities may well be the Japanese cultural-joke equivalent to our Ozark hillbillies.) Into this ranting hothouse, screaming with superstition and covered with creepy, hungry wildlife, comes a civil engineer from the mainland endeavoring to find a fresh water source so a factory can be built. Sorcery, nymphomania, incestuous temptation and guilt, monsoons, anti-drought rituals, hidden Sisyphean absurdities, ghosts, sado-masochism, crowd lunacy, and de facto marriage await him. Imamura reveals a conflicted metaphoric range here — his people are relentlessly scalded for behaving like animals, and yet the industrialization of this Pacific badland is a crime unto itself, a daunting sequence of bulldozed jungle focused finally on a disattached lizard’s tail flailing in the dirt. (Toward the beginning, a pig falls off a boat and gets savaged by sharks, and at the end a man meets a similar fate, in a reverse of the opening and closing run-amok images of Pigs and Battleships.) But Profound Desire, which was never released in this country, remains a hair-raising, richly imagined epic, filthy with unforgettable images and, by its end, beautifully mysterious.