No one would argue that Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) was not one of the most influential artist in the second half of the 20th century, if not the most. He carried on the tradition of Marcel Duchamp’s sardonically polemical sculptures and later widely expanded the definition of sculpture itself, extending it to life at large. He promoted the role of the artist as being more significant than his or her individual artworks, conducting outlandish performances that inspired Happenings and gave birth to performance art as a genre. He issued “multiples,” making his work available inexpensively long before Andy Warhol did so quite expensively.

No one would argue that Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) was not one of the most influential artist in the second half of the 20th century, if not the most. He carried on the tradition of Marcel Duchamp’s sardonically polemical sculptures and later widely expanded the definition of sculpture itself, extending it to life at large. He promoted the role of the artist as being more significant than his or her individual artworks, conducting outlandish performances that inspired Happenings and gave birth to performance art as a genre. He issued “multiples,” making his work available inexpensively long before Andy Warhol did so quite expensively.

Commemorating the 20th anniversary of the artist’s death, “Another View of Joseph Beuys: Multiples from New England Collections,” at Brown University’s David Winton Bell Gallery (through March 8), gives a survey of some of Beuys’s key themes and concerns. On display are small sculptures, prints, posters, and postcards drawn mostly from the private collection of Providence College art professor James Baker and supplemented by Brown, the RISD Museum, and other regional collections.

To encounter a large Beuys installation in a museum can be a baffling experience without being familiar with the artist’s personal symbology. By contrast, the Brown exhibition contains several works that draw on associations and connections that any viewer can make. For example, Intuition (1968) is a roughly cut pine tray with the title word penciled inside. As accompanying text informs us, more than 9000 unsigned copies were sold cheaply in Germany, available to non-cognoscenti as whimsical, metaphysical keepsake boxes.

Most of the works here are more dimensional than that, such as The Silence (1973). Five 35mm reels of the 1963 Ingmar Bergman film of the same name are stacked, the celluloid coated with copper and zinc, like battery electrodes, suggesting the potential vitality of these still objects.

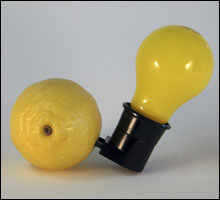

That particular leitmotif recurs in the centerpiece of the exhibition, which can be thought of as the culmination and summary of Beuys’s career. The far wall of Bell Gallery is devoted to Capri Battery (1985), one of his last creations. A yellow light bulb — the sort designed to not attract insects — is plugged into a fresh lemon. That’s all. But what an all: the humor of avoiding bugs and of a lemon producing yellow light; more significantly, the reference to drawing energy from nature (as the then dying Beuys was doing under the Mediterranean sun) and merging the technological with the natural. And so on. Curator Vesela Sretenoviæ had the entire wall behind it painted a pale yellow, and the oversized display case housing the piece is a near reproduction of how it was originally displayed.

Unmistakably recognizable as a work by Beuys is Sled #1 (1969). Comprised of a wooden sled with a felt blanket and flashlight strapped to it next to a hunk of fat, on the surface it represents a survival kit, a reminder of the difficulty and opportunity of traversing physically and spiritually in this world. But the elements here connect with Beuys’s personal mythology (reported as true in most biographies), in which as a downed pilot in World War II he was rescued in the Crimean mountains not by fellow Germans but by nomadic Tatars. Supposedly, to keep him warm they smeared him with fat and covered him with felt before hauling him to shelter on a sled.

Unmistakably recognizable as a work by Beuys is Sled #1 (1969). Comprised of a wooden sled with a felt blanket and flashlight strapped to it next to a hunk of fat, on the surface it represents a survival kit, a reminder of the difficulty and opportunity of traversing physically and spiritually in this world. But the elements here connect with Beuys’s personal mythology (reported as true in most biographies), in which as a downed pilot in World War II he was rescued in the Crimean mountains not by fellow Germans but by nomadic Tatars. Supposedly, to keep him warm they smeared him with fat and covered him with felt before hauling him to shelter on a sled.

That self-aggrandizing fantasy — perhaps a hallucination in the field hospital after his crash — comes up frequently in his work, through utilizing fat and felt. This occurs drolly at one point in this show. When Beuys first came to the states in 1974, collectors offered to buy a blackboard he was drawing on. Instead, he had the felt erasers he was using reproduced and signed. In “Blackboard Eraser (Noiseless Blackboard Eraser)” (1974), three are arrayed here next to an earlier work that simulates a blackboard. The word “Noiseless” on the actual eraser labels adds a delicious reluctance to the act of an artist wiping away his words.

A symposium addressing various aspects of Beuys’s work | List Art Center Auditorium, 64 College St, Providence | Feb 26 | 11 am-5 pm |Free | 401.863.2929

A video of Beuys’s 1974 performance “Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me” will be screened continually at the RISD Museum of Art through Feb 26

Prints will be on display in “Another View of Joseph Beuys: From a Private Collection” | Providence College Reilly Gallery, 549 River Ave, Providence | Through March 16