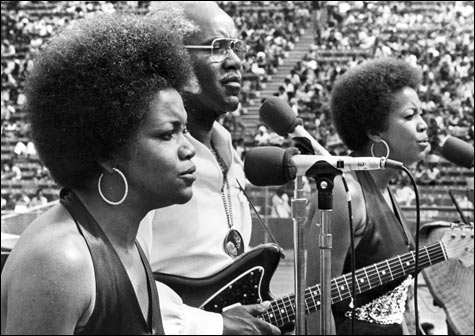

SOCIAL CONSCIENCE: The Staple Singers’ cultural hymns were about building bridges, instilling African-American pride, and enlightening whites.

|

“At Stax Records, I learned the formula for success,” says William Bell. “It was about establishing a great groove, a good melody, and writing stories that the singers could really believe in and sing with total conviction.” Bell authored quite a few of those stories, including bluesman Albert King’s “Born Under a Bad Sign,” which was covered by Cream, and his own 1962 breakthrough, “You Don’t Miss Your Water.”

The track record Stax had with that simple game plan is still the stuff of music-business legend — 50 years after its founding by a white country-music fiddle player named Jim Stewart and his business-savvy sister, Estelle Axton, who blended the first letters of their surnames to title the label. Between 1961 and 1974 Stax put 167 singles on Billboard’s pop charts and 243 on the R&B hit list.

Stax was more than a regcord company. As Rufus Thomas’s “Walking the Dog,” Otis Redding’s “Respect,” Sam and Dave’s “Hold On I’m Comin’,” and Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood” took the imprint from regional to national to international acclaim, Stax became a musical ambassador for the rise of African-American consciousness and the civil-rights movement.

Stax’s singles, like Motown’s, reached a young interracial audience. But Stax was blacker and badder. Motown catered to whites, sending the Supremes and Smokey Robinson to charm school, straightening their hair, and teaching them to speak without accents. Stax stayed unrepentantly down-home, encouraging shouters like Redding and Johnnie Taylor to phrase with gospel-blues abandon and tarring their music with greasy funk.

The just-released Stax 50th Anniversary Celebration (Stax/Concord) acknowledges all of that in two discs containing 50 of the label’s biggest smashes plus an analytical booklet by Rob Bowman, author of Soulsville USA: The Story of Stax Records (Schirmer). Not a single track sounds rusty except for Stax’s first hit, the cloying 1961 teen swooner “Gee Whiz (Look at His Eyes)” by a chirpy Carla Thomas — a tune cut when the label and the artist were just beginning to find their voice.

Former Stax publicity director Deanie Parker, who also produced some sides and wrote for the label, reports that the imprint is being revived this year and will sign new artists. “We don’t think the Stax name has lost any of its vitality. It still means a great deal to a lot of people in terms of absolutely timeless music and in terms of community.”

Parker is in part responsible for that. She was the label’s first African-American hire — Estelle Axton’s right-hand woman — and as the chief officer of Soulsville USA: The Stax Museum of American Soul Music, in Memphis, Tennessee, she’s become the de facto custodian of the Stax legacy.

Even after Stax Records shut its doors, in 1975, it never went away. The Stax sound — a powerhouse bottom end, horns playing ensemble riffs and bridges, spare arrangements, vocals front and center, gospel singing and instrumental techniques, and the kind of delayed backbeat that Muddy Waters first made popular on vintage Chess blues recordings — has continued to reach subsequent generations of listeners. The label’s catalogue has been tapped hundreds of times for films. Rappers including pivotal figures like Big Daddy Kane and the Geto Boys have sampled the raw energy of such Stax thoroughbreds as Booker T. and the MG’s, who were the label’s house band plus hitmakers in their own right, and the great arranger, songwriter, and producer Isaac Hayes, whose progressive social and musical agenda earned him the nickname “Black Moses” decades before he was South Park’s “Chef.” Every musician who plays funk, soul, hip-hop, R&B, and a myriad of other musical styles almost surely has some element of the Stax sound in his or her chemistry.

“Stax is deeply embedded in the musical DNA of Americans,” says drummer Billy Martin of the jam-funk-jazz trio Medeski Martin & Wood. “It’s a huge part of our language. Growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, Stax just seemed to be what music was — the coolest soulful, funky, American hit music. I remember putting on the Shaft theme in my room and acting out in my leather jacket, feeling so cool, like being in the movie with the soundtrack fueling my character. I wouldn’t be nearly as funky if I didn’t grow up listening to this stuff.”

Many of Stax’s classic releases also had a subtext, and the warm psycho-acoustic appeal of the label’s sound let it sink in. Tunes as different as Rufus Thomas’s percussive “Do the Funky Chicken,” which Thomas contended was a progenitor of rap, and the Staple Singers cultural hymns “Respect Yourself” and “I’ll Take You There” were about building bridges, instilling African-American pride, and enlightening whites. Thomas’s smash inspired an arm-flapping dance craze that crossed America’s racial divide by bringing all colors to the floor and uniting them in plain, silly fun. And the Staples’ affirmations of bootstrap pride reflected the strength and aspirations of African-Americans who were shedding the rule of Jim Crow and worked as a window into the collective mind of rising black consciousness and power. Consider that in 1971, the year “Respect Yourself” was recorded, Memphis decided to close down public swimming pools rather than let blacks and whites beat the sweltering Delta heat in the same water.