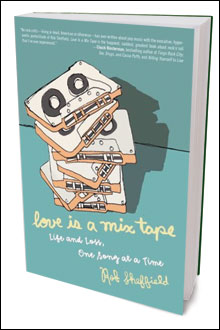

Critic Rob Sheffield comes to terms with the death of his musical soul mate in Love Is a Mix Tape

SMITTEN: There may have been some crappy music in the ’90s, but Rob’s love for Renée made it all sound sweet.

|

If every generation has its Love Story, its tragic tale of romance and loss, then Rob Sheffield’s Love Is a Mix Tape is that book for those who came of age with indie rock. Sheffield, a contributing editor for Rolling Stone, ostensibly wrote Mix Tape because his wife, Renée Crist, died unexpectedly and way too soon (age 31) on May 11, 1997, of a pulmonary embolism. But more than a meditation on grief, this is a love letter, both to the iconoclastic fellow critic Sheffield adored and to the rock that served as the soundtrack of their five years together.

Although the essential romance may be timeless, this is a book of its time, almost aggressively so, as Sheffield charts his life before Renée and their years together through popular culture. There are, first and foremost, the mixtapes of the title. One heads each chapter, and at least a partial discussion of the music, or the occasion for the tape’s creation, makes up some of the text. Sheffield is, after all, a critic, even if he was an English grad student with academic dreams when he and Renée first met, and bonded to Pavement, in Charlottesville.

But before he gets to their romance, as if to explain his double loves, he provides an amusing overview of his youth as a gawky Boston Irish Catholic kid who came alive through music and finally realized that music was more than a crutch, it was a major part of life. As he skims through these early days, not even his first romance is immune. Dumped and down, he comes to terms with his true values: missing his girlfriend, he is “sad.” But really, he acknowledges, “I loathed myself for secretly wishing I’d taped her records before she ditched me.”

By the time he and Renée meet up, it’s clear they share this passion. Like the music nerd he is, Sheffield introduces Renée through her music creds. “Her favorite song was the Rolling Stones’ ‘Let’s Spend the Night Together.’ Her favorite album was Pavement’s Slanted and Enchanted.” Big Star, George Jones, Yo La Tengo, and Marshall Crenshaw all vie for space on Renée’s tapes.

What makes this book stand out, though, are not the band names and titles but the vibrancy of the couple’s time together. When Sheffield gets past the initial lists, Renée becomes fully fleshed and their love is palpable, if completely pop-referenced. He sings the Pips’ back-up to her Gladys Knight; she interviews L7 for Spin and comes back with make-up tips. Even the couple’s wedding is described in terms of a scene in The Godfather. “You did good, Enzo,” quotes Sheffield, describing the two young people shaking at the altar.

If this sweet, lively, affecting book slips up at all, it’s that its author confuses his relationship with the era. Much of the music was good, as his memories make clear; as he also makes clear, some of it was crap. Instead of seeing that those years shone because of love, because of their shared youth, he credits the pop culture that provided its soundtrack. “There’s a lot I miss about the nineties,” he writes. “It was an open, free time of possibilities, changes we thought were permanent.”

He’s closer to the mark when he talks about the days after Renée’s death, when he sought to thank everyone who had contributed to her full-throttle life. “What I wanted to do was simple: write notes to people, say thank you for making Renée’s life better, you made her happier, you took care of her. . . .” Overwhelmed by his own loss, he abandons this project after two such missives. This book serves the purpose of, as REM sang, those letters never sent.