SÁTÁNTANGÓ: A single, harrowing, ass-in-seat experience. |

Let’s take stock of Béla Tarr, the great Hungarian dyspeptic, and maybe the most famous and revered international film titan to have been so pitifully screened in American theaters that his public profile here is tantamount to an embargo. One of the planet’s great cinematic formalists and, with Theo Angelopoulos and Aleksandr Sokurov, one of the reigning masters of the immersive, hyperextended tracking shot, Tarr has a wedge of territory all to himself — apocalyptically run-down, dead-or-dying post-Communist villages on vast Mittel European plains of mud, poverty, crushed will, delusionary behavior, and charcoal skies, all observed by a cinematographic point of view that stalks silently and patiently through the ruins like a ghost. To label Tarr, co-subject of this week’s micro-retro at the Harvard Film Archive, as a downer is merely a philistine’s impatient way of saying he’s an existentialist, a modern-film Dostoyevsky-Beckett with a distinctly Hungarian taste for suicidal depression, morose self-amusement, and bile.In this he’s not sui generis, but his mise-en-scène — his capacity to limn out entire environments in long one-shot sequences that encompass breathtaking coincidence and natural phenomena without seeming gimmicky or over-planned — is moviemaking at its bravest and movie watching at its most galvanizing. Looking over the development of post-Antonioni film culture, you could see shot length in itself as a kind of cultural palmistry: American filmmakers favor control-crazy brevity, but for a certain breed of cinéaste in Western Europe, where memory of the past weighs on life like cloud cover, the syntax of the real-time, spatially expressive tracking sequence is the way movie time should be constructed. For Russian wonder Mikhail Kalatozov, the whole world captured in a single motion meant our righteous empathies had nowhere else to look; for Tarr precursor Miklós Jancsó, breadth and length were ways to understand the canvas of war. Andrei Tarkovsky’s moody set-ups were metaphysical questions, growing less answerable the longer they became. Greek master Angelopoulos’s stock-in-trade mega-shot is a translation of history into visual experience.

Tarr is the only notable director for whom the giant one-shot scene is a turning inward, a dance between philosophical pessimism and the desperate actualities of life that press down upon it. It wasn’t always so: he began as a hard-bitten, post-Cassavetes realist, working in the mid-’70s subgenre known in Budapest as “documentary fiction.” He began to experiment with long takes and distance in 1982, with a TV version of Macbeth; his previous three features, all out on DVD from Facets, are a different species altogether, intimate, urban, desultory, and inflamed with class rage. Family Nest (1977), a spiteful, multi-generational drama of life on the dole, was the film Tarr made before he went to film school; The Outsider (1981) traces the aimless social descent of an off-the-grid violinist more concerned with boozing than with holding a job. Prefab People (1982) is an unrelenting, smell-the-sour-breath portrait of a blue-collar marriage dissolving under pressure from Communist-era poverty, masculine inadequacy, and restless depression.

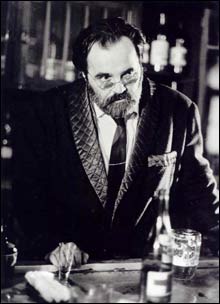

DAMNATION: Some of the most magnificent black-and-white images shot anywhere in the world. |

It was only with DAMNATION (1988; January 12 at 6:30 pm + January 17 at 9:15 pm), and Tarr’s interface with acclaimed Magyar novelist László Krasznahorkai, that things became recognizably Tarrian. This small-framed film — modest at least relative to the subsequent epics SÁTÁNTANGÓ (1994; January 12-13 at 2 pm) and WERCKMEISTER HARMONIES (2000; January 12 at 8:45 pm + January 17 at 6:30 pm) — traces the self-destructive lives of two men and a weary bar chanteuse in a dead mining town where anomie and liquored exhaustion infect their lives like a virus. As shot by Tarr comrade/superhuman cinematographer Gábor Medvigy, it’s a serotonin-depleted ordeal, and something of a lovely sketchbook of vibes and ideas to come, with some of the most magnificent black-and-white images shot anywhere in the world.Considering Krasznahorkai’s role in the creation of Tarr’s most famous films is a dicy maneuver — as is any prognostication pertaining to who’s responsible for what in a collective project we didn’t witness. Damnation, for instance, began not as a novel but as a screenwriting collaboration between the two men, at a time when Krasznahorkai had published only two novels (the first of which was Sátántangó). Only the later novel and the source for Werckmeister Harmonies, TheMelancholy of Resistance, has been translated into English, and by the look of it the author’s prose approach is more matter-of-fact, more internal and ruminative, and more historical. There’s no hint of the solemn, monumental, nearly abstracted poetry that we see in Tarr, and though Krasznahorkai’s sentences are rich and ropy, much of the novel’s political material and specific social commentary goes missing in the film. A single descriptive page can turn into a monumental 12-minute set-piece in the Tarr film, minus its psychology and real-world context but plus an unforgettable saturation in space and time. All the same, you could hardly nail it down as a case of a crazed cinéaste mutilating a novelist’s vision — Krasznahorkai co-wrote the screenplays, and the film of Sátántangó, for one, took many years for the impassioned partners to get produced. We can assume that the metamorphosis from book to film was understood by the writer as a crafting of a new and radical art object, beside which the novels independently sit, retaining their own, very different form and voice.