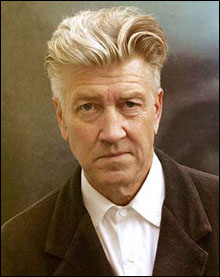

David Lynch, circa now

|

It will be a rare soul can watch David Lynch’s American-surrealist mystery movie, Blue Velvet, without wondering, at least for a moment, What It All Means. The last one offering any clues is Lynch himself. Ask the 40-year-old director of Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, and Dune to ruminate on a scene from his latest film, and he’s apt to give you a quizzical stare (a smile tugging at the corners of his mouth) as he offers the sort of blandly matter-of-fact reply you’d expect to hear from a cabinetmaker. The message is clear: Lynch wants his films to be experienced – not explained. “I don’t understand them any more than anybody else,” he says. “I get ideas, and they thrill me, and I fall in love with them and start trying to bring them out and arrange them. And so many things are…surprises, to me. The things that bob up.”

Things? Ideas? The way Lynch talks about his dreamy, disturbing visions, he can sound like the Gary Hart of outré cinema. Yet it’s easy to understand his reticence: for a man who works closer to his unconscious than perhaps any other filmmaker today, trying to pin down those “ideas” would be bad karma. As he puts it, “If you start analyzing them, you sort of kill them.” A lot of people who meet David Lynch are startled to discover what a conventional fellow he is. Clad in a natty woven jacket, his thick brown hair impeccably groomed and his shirt buttoned to his Adam’s apple, this tall, trim, handsome gentleman who greets you with a firm handshake seems every inch the new-wave preppie. There is, though, something almost subliminally eccentric about him. It’s his voice – a high, intellectual whine (sort of like Wally Shawn’s) that lends him an aura of cultivated nerdiness. One senses that Lynch’s “normality” is partly a mystique, a finely honed surface that counterpoints his untamed imagination.

That’s what Blue Velvet, with its dark-yet-gleeful portrait of a North Carolina small town undermined by kinkiness and dread, is about. Although the movie’s atmosphere cuts directly across eras, it is rooted in the ‘50s, in the sort of pristine Life-magazine environment Lynch grew up in. “I come from the Northwest,” he explains, “a world where everything was, you know, so perfect. I was born in Missoula, Montana, but the town I picture as being perfect was Spokane, Washington. And when you have that dreamy sort of childhood, and then you come to Brooklyn to visit your grandparents – well, I felt sort of fear or tension or something in the air that was so different from what I knew. And that was a very powerful thing.” That Brooklyn visit is one of Lynch’s favorite anecdotes; another is the story of how he spent the late ‘60s in a deserted industrial section of Philadelphia, living with his first wife in a three-story house that was kitty-corner from the local morgue. “I saw horrible things pretty much every day,” he recalls. “I thought I’d never get out of there, ever. There was tremendous fear in Philadelphia.” That fear, that something in the air, was translated into gnawing, comic anxiety – the suspended-in-midair queasiness – that is the operative mood of Eraserhead and also figures into Blue Velvet. Lynch relates that mood to his childhood as well. “There’s a sort of innocent, naïve thing about the ‘50s, and then a cold, troublesome power that was underneath it all the time. It’s becoming stronger now; more people are aware of it. But in your regular life, out and around, many things remain hidden in yourself and your environment.”

In Blue Velvet, those hidden forces erupt most memorably in Dennis Hopper’s Frank, a furious psychopath who acts his sexual sickness on the masochistic Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini) and also takes the hero, Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan), on a bizarre, terrifying “joyride.” “It goes back to an American sort of archetype,” says Lynch of the Hopper character. “He’s the guy in town who’s potential trouble for anyone who crosses his path. Everyone has maybe seen this person, or somewhere inside them they know that kind of person.” Hopper gives a major performance, but the most hypnotic scene in the movie may belong to Laura Dern’s sweet, innocent Sandy, who delivers an extraordinary speech about love and robins. Is Lynch equally possessed by the forces of goodness? “Yes, absolutely. People become, I think, almost more uncomfortable in that scene with Sandy than they do when Frank is doing his thing to Dorothy. Those kind of naïve, innocent, idealistic notions, they’re not so cool, but for Sandy, and even for Jeffrey, too, in their car on the street – you know, you say some goofy things, but I think people still believe those things somewhere.”