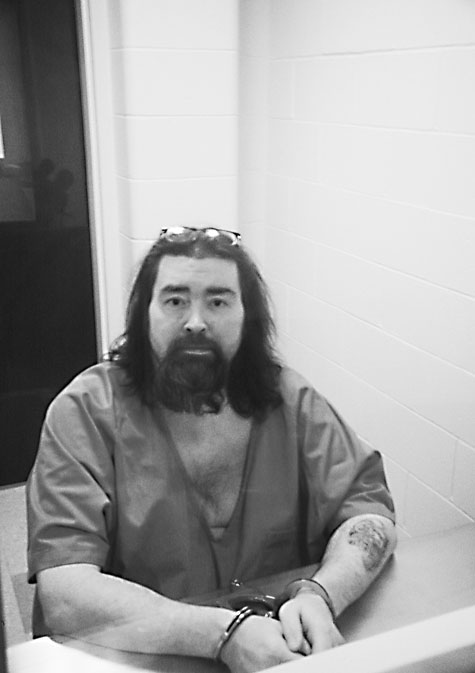

Deane Brown, whistle-blowing prisoner |

Vacillating between grit and despair — between aggressive lawsuits and suicide attempts — Deane Brown, the prisoner who in 2005 blew the whistle on the torture of mentally ill inmates at the Maine State Prison’s solitary-confinement “Supermax” unit, is struggling against prison conditions in Maryland, where he was exiled by the Baldacci administration. (See “Baldacci’s ‘Political Prisoner,’” by Lance Tapley, November 21, 2006.)

In August, Brown was transferred from Western Correctional Institution in Cumberland to North Branch Correctional Institution, also in Cumberland, which houses many of Maryland’s most serious offenders. When sent to Maryland in 2006 he first had been put in the state’s Supermax, in Baltimore.

Brown was given no reason for the recent move, but his Maryland inmate-legal-aid lawyer, Joseph Tetrault, says prison authorities view him as a troublemaker. According to his Rockland friend Beth Berry, who has talked with him on the phone, in North Branch he has already been “jumped and assaulted by three men in the shower.”

An intelligent and tolerant man, well liked in Maine by both inmates and guards, Brown, 45, has resisted what he calls “rampant” racism in Maryland’s prisons and has refused to join gangs. At Western, he tried to take a law correspondence course paid for by a Maine supporter, but had to abandon it. In a letter to a school official, he explained: “I have tried to move out of a cell I share with a racist. He seems to think he can convince me to believe, as he does, that being white makes me more human than those who are not. We constantly argue and sometimes fight. I cannot study or even sleep regularly.”

He has also complained about the Maryland system’s treatment of his diabetes, at one point obtaining a court order requiring the prison to ensure he is given food soon after an insulin injection. He also received $2500 in damages because of the prison system’s neglect. But Brown reports the judge’s order has been ignored and he is still at risk of going into diabetic shock from low blood sugar if he isn’t given food in a timely manner. As he testified in one court proceeding:

“When I’m laying on the floor, sweating profusely, urinating all over myself, vomiting, the nurse finally comes in. . . . She’s screaming give him something to eat, now, and I’ve been screaming for three hours to get something to eat. That’s an imminent fear of death right there for me.”

He has at times refused to accept the insulin if he isn’t given food properly, but the judge also has ruled injections can be forced on him. Tetrault has appealed this ruling to a higher state court, with a December hearing expected.

Brown struggles with despair over both his personal condition and conditions he witnesses. “People get Maced and beaten regularly over here, for little or no reason,” he wrote in a letter to Tetrault, about the Western prison. By his own reports he has tried to kill himself twice.

“Maine threw him to the wolves,” Berry says.