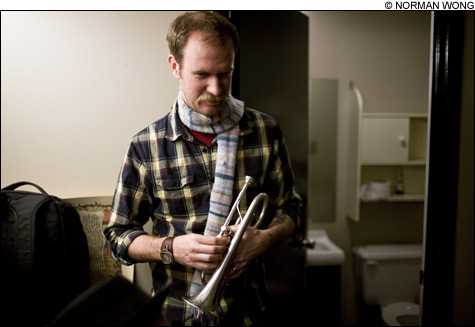

FREE SPEECH From the rhythms and pitches of his neighbors’ recorded talk, Charles Spearin created music for a live band.

|

Charles Spearin's Happiness Project — to be performed this Friday at the Middle East Downstairs as part of a trio of Torontonian acts — was originally just that: a project. Since 2007, Spearin has been recording conversations with a handful of his neighbors — combing through each of the resulting clips with one ear on their content and the other on their sound, trimming them down into accidentally musical excerpts, scoring and arranging their inbuilt melodies for various instruments, and constructing fully arranged compositions around the natural rhythms and melodies of human speech. The scores are then taught, syllable by syllable, to a live band.

I know. Crazy, right? He actually talked to his neighbors!

Spearin resides in a little house in downtown Toronto, not far from Little Korea and Little Italy. He's been in his current house (where the HP was realized) with his wife and two kids for the past five years, but he grew up just a few blocks away — and his wife grew up across the street. Through the balmy city summers, the Spearins spend much of their time making up for the long winters, lazing on their front lawn, watching the kids topple over in the grass, eating their dinner on the porch. Sometimes Mrs. Morris would pass by and say hello before heading into her house across the way, and Spearin would secretly marvel at the sound her hellos made.

If all this sounds just a little too darling to believe, keep in mind: Canada. But also: Spearin is not your average neighbor. A founding member of exalted pop clusterfuck Broken Social Scene and cerebral post-rock shape-shifters Do Make Say Think, he's got a keen, ever-ready ear for melody — wherever it might turn up.

Spearin's interest in language as unwitting instrument isn't entirely new; the last 100 years of contemporary poetry, for example, owe greatly to the breath-measured verse of Charles Olson and the faithful American colorations of William Carlos Williams. But for his part, Spearin's inspirations were fundamentally musical — he cites composer Steve Reich, who pursued "speech melody" through the '90s with works like Different Trains, in which spoken testimony from Holocaust survivors provides rhythmic units for the piece as a whole. But Spearin's inspirations were also personal.

"Originally, I was just hoping to find some interesting melodies," he says. "The interviewees were almost like guinea pigs — let's bring them over and have them say stuff!" It wasn't long before an unexpected complication arose: "Then they started saying really profound things. I had to re-evaluate my intention. Everything became about the words."

As his sources — Mrs. Morris, one Mr. Gowrie, a young girl named Ondine, a deaf woman named Vanessa — graduated into subjects, Spearin felt his process turning into a project. Preserving the emotional and autobiographical heft of his interviewees' responses required the boosted sensitivity of a documentarian. And even as he found that the melody of unrehearsed speech (more often than not) bore uncanny compatibility with its meaning, experimenting with harmonic structures around these recordings required letting that melody lead the way and adding only that which naturally fit. Spearin compares the assembly of these songs to a crossword puzzle.