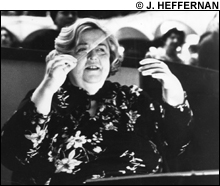

When the curtain went up at Boston’s Back Bay Theatre for the American premiere of Arnold Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, in November 1966, two figures were standing back to back in a spotlight on a small disc. This simple image was a profound emblem of what Schoenberg’s difficult and challenging opera was about, Moses and Aaron as two halves of the same person: the tongue-tied visionary and the easy talker who could communicate his brother’s vision. Sarah Caldwell, the director of that production, was a visionary who could also communicate her vision. This was one of countless memorable images that are part of her legacy. Last week, she died of heart failure at the age of 82, in a hospital in Portland, Maine, after years of health crises.

When the curtain went up at Boston’s Back Bay Theatre for the American premiere of Arnold Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, in November 1966, two figures were standing back to back in a spotlight on a small disc. This simple image was a profound emblem of what Schoenberg’s difficult and challenging opera was about, Moses and Aaron as two halves of the same person: the tongue-tied visionary and the easy talker who could communicate his brother’s vision. Sarah Caldwell, the director of that production, was a visionary who could also communicate her vision. This was one of countless memorable images that are part of her legacy. Last week, she died of heart failure at the age of 82, in a hospital in Portland, Maine, after years of health crises.

Her last production for her Opera Company of Boston was the world premiere of Robert DiDomenica’s The Balcony, in 1990. It was one of her three world premieres, along with a dozen major US premieres of operas by composers as diverse as Rameau and Prokofiev, Verdi and Roger Sessions, Berlioz and Peter Maxwell Davies, plus the American premieres of Mussorgsky’s original orchestration of Boris Godunov, Verdi’s original French version of Don Carlos, and the original versions of Gounod’s Faust and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

I started going to Caldwell’s productions in 1964 — already the sixth season of her “Opera Group.” She was giving Alban Berg’s Lulu — a landmark 20th-century opera — its East Coast premiere, years before the Metropolitan Opera got around to it. It was a brilliant, daring, chilling success, with its black-and-white newspaper sets by designer Rudolf Heinrich, and the late Osbourne McConathy conducting, with Joan Carroll as the seductive Lulu and opera legend Blanche Thebom as the lesbian Countess Geshwitz.

When the Back Bay Theatre was torn down, Caldwell, faced with traveling in the wilderness, found imaginative — often stunning — solutions to the problems raised by each new and uninviting venue. In Charpentier’s Louise (1971), she turned the Cyclorama (the former Boston flower market) into Montmartre, with jugglers, acrobats, and street vendors crowding the aisles. (Hollywood’s Tommy Rall was the lead somersaulter.) At the climax, a simple spotlight focused on a rotating mirror ball high up under the glass dome of the Cyclorama turned Montmartre into a gigantic swirling carousel we were all riding! In 1970, MIT’s Kresge Auditorium became the Flying Dutchman’s ship (Thomas Stewart and Phyllis Curtin had the leading roles), and Caldwell used the Rockwell Cage to brilliant effect, with the audience on both sides of a central runway, for Robert Kurka’s satirical Good Soldier Schweik. She made witty use of Tufts’s Cousens Gymnasium for Beverly Sills in Donizetti’s La fille du régiment. It’s called “total theater,” and Caldwell was a master. No opera company in the country was producing work on this level of inspiration and excitement. Boston was the opera capital of the USA, and Caldwell made the cover of Time.