|

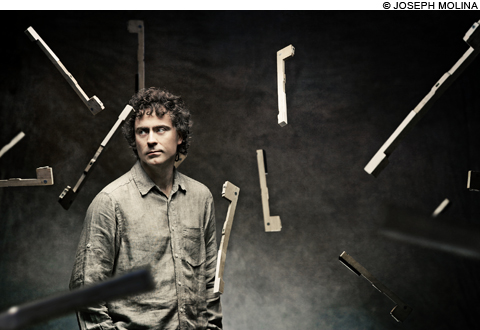

Even in a city like Boston with so many stars in its musical firmament, concerts in which great musicians triumphantly tackle the very greatest literature is still rare. But doing just that was the 40-year-old British pianist Paul Lewis, playing Schubert's final three piano sonatas in his first public appearance here, presented by the Celebrity Series of Boston (two years ago he gave a memorable Schubert recital for the members of the 175-year-old Harvard Musical Association). These astounding pieces, composed only a month before Schubert's death at 31, are among the most challenging in the entire keyboard repertoire, and among the most beautiful and moving. A numbered sequence, they were evidently conceived as a set. Not many pianists dare to play all three of these large-scale works on the same program. But hearing them together, they seem a kind of Divine Comedy: by turns — and even more astonishing, often simultaneously — heroic, tragic, profoundly spiritual, achingly poignant, demented, and even cheerfully comic. And how amazing to hear an artist like Lewis capture all of these qualities.

Schubert's sonatas remained relatively unplayed until Artur Schnabel rediscovered them and recorded the last two in the early 1930s — still the gold standard. Robert Lowell once called the C-minor Sonata Schubert's requiem for himself. Powerful but static opening chords suddenly turn into a headlong race. Scintillating arpeggios — falling and rising — seem like lightning bolts fired from the beyond (down from Heaven? up from Hell?). The fourth movement is a Death Dance that becomes a Death Ride — a wild cross-hand gallop (harking back to Schubert's early song "The Erlking"?), with more of those descending runs raining down before the return of the majestic, ominous opening chords. Lewis played with power and tenderness, grandeur and intimacy, in seamless continuity.

That sense of coincident rising and falling continues with even greater complexity in the A-major Sonata, which begins as a hymn but soon reveals more complicated spiritual turmoil. The hushed slow movement is a piercing song in F-sharp-minor, maybe even more "minor" in mood than anything in the C-minor Sonata, with a cataclysmic interruption in the middle. The sprightly Scherzo is crossed with shadows. In the Rondo finale, a catchy theme returns with increasing ethereality. Then something uncanny: brief fragments of memory, reminiscences of earlier themes, break the forward movement, each interruption followed by a sudden breathtaking stop. Until the final onrush. Here too, Lewis's pace and timing were impeccable. Both earthy and otherworldly, his playing had both weight and weightlessness.

The B-flat Sonata is generally regarded as Schubert's greatest. And Lewis didn't falter. He found a way to make the paradoxical first movement tempo marking — "molto moderato" ("extremely moderate") — completely convincing, deliberate yet unstoppable, the solemn opening song suddenly undermined by growling low tremolos that ominously recur throughout the whole piece. The funereal slow movement pits doubt against triumph. Neither prevails. In the vivacious Scherzo, are the gods laughing? And in the mysterious finale, a repeating note warns that time is running out, a fear that Schubert also celebrates.

Last summer, Lewis made his BSO debut at Tanglewood in a heavenly Mozart 23rd Piano Concerto under Christoph von Dohnányi. Considering how new he is to these parts, it must have been a pleasant surprise for the Celebrity Series to find this Schubert recital filling Jordan Hall almost to capacity. And given the warmth of the response, on both these occasions, I wouldn't be surprised to see Paul Lewis on future BSO and Celebrity Series programs. I wouldn't complain, either.