ROBOT LOVE Emotionally complex and intellectually ambitious, Death and the Powers is hobbled by theatrical and musical missteps. |

In her director's note for the American premiere of Death and the Powers: The Robots' Opera, which was composed by Tod Machover, with a libretto by poet Robert Pinsky, Diane Paulus, artistic director of the American Repertory Theater, wrote that this "work of music-theater . . . has brought together artists from the widest range of disciplines — from theater and film to modern dance and the cutting-edge technology of the MIT Media Lab." Paulus's failure to mention the two most essential figures in the creation of an opera — the composer and the librettist — manifested itself in her production, in which the cute robots got more applause than the outstanding human performers. Even the gauche new subtitle, "The Robots' Opera," feeds into the pre-performance publicity focused almost exclusively on the electronics. What kind of "music-theater" is Paulus selling? The opera is emotionally complex and intellectually ambitious, though at the Cutler Majestic on opening night (the final performance is this Friday, March 25), it was less satisfying than what I saw on the video of the world premiere in Monaco last fall.

.jpg) |

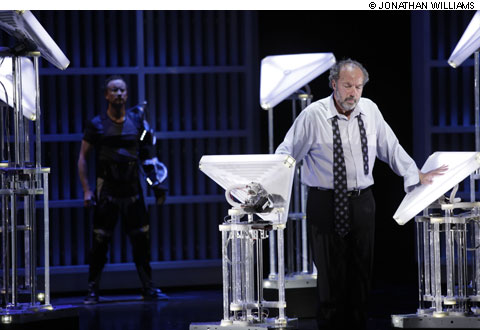

Pinsky's moving and verbally playful libretto tells the story of a beyond-wealthy but dying entrepreneur named Simon Powers. (Even the title of the opera is a pun.) Refusing to accept his death, he allows himself to become absorbed in an electronic "System" in which he can "live" — bodiless — forever. His young assistant, Nicholas (the refined and athletic tenor Hal Cazalet), almost an adopted son, whom he'd rescued from a ward for severely disabled children, is ready to join him, and his third "and best" wife tunes into his new incarnation on headphones. Only his daughter, Miranda (shades of The Tempest), is not sure she wants to give up her body and all its limitations in order to join him in immortality. This is all bracketed by a prologue and epilogue in which the robots of the future ritually act out their pre-history, though they no longer understand even the concept of Death. Powerful stuff.

Machover's music, which combines a live orchestra (the splendid Boston Modern Orchestra Project, conducted by Gil Rose) and "live" electronic manipulation by a team from Machover's Media Lab, is also powerful — maybe too powerful. Pinsky's text has a poet's mercurial wit and constantly shifting tone. Powers (the phenomenal baritone James Maddalena — Nixon in China's original Nixon) sings Yeats's lines in "Sailing to Byzantium" about becoming an immortal golden bird, then a moment later flips Yeats the bird. But Machover's score is less flexible from moment to moment. The tone doesn't change on a dime. Several times, the music actually emphasizes the wrong word. (When Powers disappears into the System, for example, the real question is "Are you there?" not "Are you there?")

The music for the robots that begins the opera sounds like a horror-film soundtrack, and the robots declaim their lines like pompous doomsday-movie narrators. Their voices are amplified, which heightens the disembodied, mechanical quality. But then, everyone's voice is amplified — and disembodied. This emphasizes the idea that everything that follows is the "robots' opera." And since the singers have not been directed to display convincing human interaction, there's a huge cost to this distancing of the audience from the human drama. The amplified singing steamrollers the listeners, and aiming glaring lights into the theater (where haven't we seen this before?) just continues the assault.