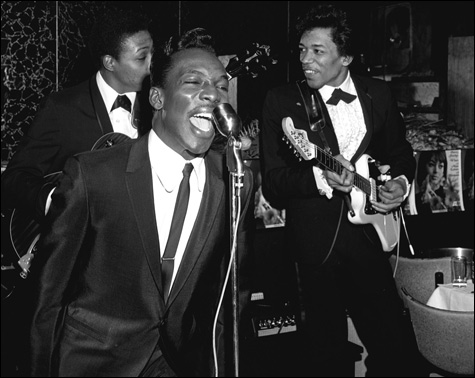

MIDNIGHT HOUR: William “PoPsie” Randolph caught Wilson Pickett with his back-up duo, which included, at right, Jimi Hendrix. |

| “Selections from Who Shot Rock & Roll: A Photographic History, 1955 to the Present” | Worcester Art Museum, 55 Salisbury St, Worcester | Through May 30 |

It is May 1966, in the Prelude Club in Harlem, an Atlantic Records release party. Wilson Pickett, who had released “In the Midnight Hour” the year before, appears super suave, with his hair slicked up and back, his pencil moustache, and his sharkskin suit and thin tie. He leans into a microphone and lets loose.Behind him stand two guitarists, loose and laid back in contrast to Pickett’s hot-coal intensity. In William “PoPsie” Randolph’s photo of that moment — which is part of the Worcester Art Museum’s “Selections from Who Shot Rock & Roll: A Photographic History, 1955 to the Present” — you might recognize the guitarist on the right, in a neat suit and bow tie, as Jimi Hendrix. The only signs of the later psychedelic-guitar god, aside from that familiar smile, are his pompadour, ruffled shirt, and left-handed guitar.

In June the following year, Hendrix performs at the Monterey Pop Festival in California. He is transformed, now wearing a hippie vest, rings, an Afro, and an extravagantly ruffled shirt. Seventeen-year-old Ed Caraeff, who’s seated at the edge of the stage, has never seen or heard Hendrix before. It is still two months before his debut album, Are You Experienced, will be released in the United States. But as Hendrix sets his guitar on the stage and squirts it with lighter fluid, Caraeff stands on his chair and clicks away with his camera.

Shown here are four shots: Hendrix spraying the guitar, Hendrix kneeling on the stage and lighting a match, Hendrix spraying more fluid onto the burning guitar, and Hendrix kneeling before the guitar as if in worship and fanning the flames. That last one, which became a holy icon of rock and roll, was the final frame on Caraeff’s roll of film.

Randolph’s photo of Pickett and Hendrix balances on the tipping point between one era and the next. Randolph had photographed jazz greats from Louis Armstrong to Billie Holiday (and had been a band manager for Benny Goodman) before adding rock stars to his repertoire. His shot follows the classic jazz imagery of nattily attired cool cats in cozy, cramped subterranean clubs. Jazz photos tend to be inwardly focused, possessing the music’s sense of improvisation, but under expert control. Rock-and-roll photography is about exploding, about things getting out of hand. Maybe the difference comes down to the proud, upright stance of a jazz trumpeter versus the swaggering slouch of a rock guitarist — an emphasis on head, fingers, and lungs versus arm and crotch.

“Who Shot Rock & Roll” was organized by photography historian Gail Buckland for the Brooklyn Museum of Art. (Buckland has also published the show in book form with Knopf.) The Worcester version of the show offers more than 100 photos of artists, among them Buddy Holly, Janis Joplin, the Velvet Underground, Bob Marley, Joy Division’s Ian Curtis, the Notorious B.I.G., and Amy Winehouse.