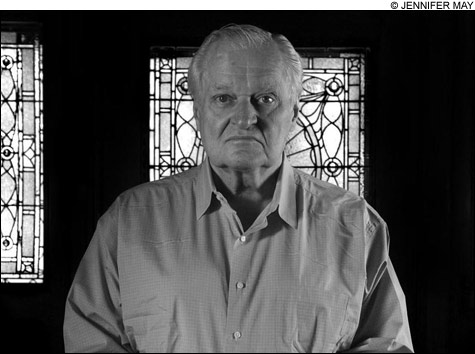

HOW AND WHY: The poet who once yanked the meter of a Peaches & Herb song is still playful — though sometimes perilously. |

| Planisphere: New Poems | by John Ashbery | Ecco | 160 pages | $24.99 |

So understood is John Ashbery's post at the top of the contemporary American poetry heap (a distinction these days with the cultural heft of a Scrabble championship) that the question of just how to read him seems doomed to languish beside the point. Detractors need only a pillow and a trusty alarm clock to approach Ashbery. But to fans (and a generation of imitators), interpretive guidelines run the gamut from appreciating his language as one might music to gazing into it as one would the night sky — perhaps with a planisphere for bearings.At 81, Ashbery is going strong, as his plump new volume of 99 alphabetically ordered poems demonstrates. But can the same can be said for his readers? After all, as the ones charged with the task of making meaning out of his poems, we share a large stake in his triumphs. What authority he has accumulated he routinely cedes to the reader — and as charitable as that sounds, it's a lot more work than most of us sign up for. If it is indeed true that there's no wrong way to read an Ashbery poem, and if all of the various methodologies pointed at his purported difficulty are nothing more than coping mechanisms, it seems fair — since he's now a canonical given — that we promote our questioning from how to why. Of course, with Ashbery, the part of why is always played by how — that is, the journey is the destination, the process is the form. Or, as he puts it at the end of "Just How Cloudy It Can Get": "Makes sense to me./Make sense to you?"

When I was a student, my trick for wicking cognitive satisfaction from Ashbery's work was to scan closing lines for bits of thesis. It served my irritating need for coherence well when I first read 1956's Some Trees. At the close of "The Painter," "the subject has decided to remain a dream," and in "Some Trees," the "accents seem their own defense." Like large swatches from a torn map, they felt vital to something, though I may never see the whole of it.

With Planisphere, this tactic doesn't work so well. Ashbery finds himself often with nothing to say, but always with nothing to hide. "Banish truth-telling," he says in "Boundary Issues," "That's the whole point, as I understand it." "Giraffe Headquarters" offers an optimistic glimpse into his poetics: "Try this, but only for a while./If it works, you can be said to have lost nothing,/which is what winning is." But that has a naive counterpart in the grim finish of "The Person of Whom You Speak": "Work, win, suffer some more."

The poet who once yanked the meter of a Peaches & Herb song is still playful — though sometimes perilously. "FX" is a hoky cobble of archaisms; "They Knew What They Wanted," a composite of movie titles, is banal anaphora; "Zero Percentage" rushes to damn itself ("The title always wins."). But despite hammy extremes now and then, Ashbery helms a keen awareness of himself throughout, as in "Breathlike": "Just as the day could use another hour,/I need another idea. Not a concept/or a slogan. Something more like a rut. . . . "