Photos from Yousuf Karsh, William Christenberry, and the PRC

By GREG COOK | November 14, 2008

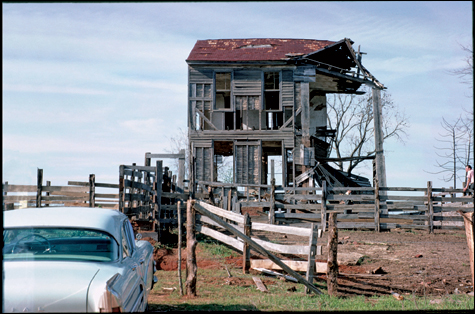

OLD HOUSE, NEAR AKRON, ALABAMA (1964): The soul of Christenberry's photography is in his

Southern Gothic subjects, not his compositions. |

Photos: Yousuf Karsh, William Christenberry, and the PRC "Karsh 100: A Biography In Images" | Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave | Through January 19 "William Christenberry: Photographs, 1961-2005" | Massart, 621 Huntington Ave, Boston | Through December 6 "Keeping Time: Cycle And Duration In Contemporary Photography" | Photographic Resource Center, Boston University, 832 Comm Ave, Boston | Through January 25 |

You might say Yousuf Karsh was a one-man golden era of portrait photography. In "Karsh 100: A Biography in Images," which is now up at the Museum of Fine Arts, his iconic shots of Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, and Ernest Hemingway are defining portraits of the men in all their crusty manliness. And check out his willowy profile of Audrey Hepburn, the craggy face of Boris (Frankenstein's monster) Karloff, and a smoldering Anita Ekberg, eyes closed, smiling, hair blowing across her face, bosom thrust forward.MFA photo curator Anne Havinga brings together more than 100 of Karsh's photos. The time line runs from his apprenticeship in Boston (1928-'31) to setting up his own business in Ottawa (1932) to his great success photographing for Life magazine and other major publications to his return to Boston (1997 until his death in 2002). It's a seductive star-studded show.

The development of photography in the 19th century made realist painting really, really uncool for a long time, and it cleared the way for photography to be the primary medium of portraiture in the 20th century. Karsh had the good luck to arrive on the scene just as advances in printing were fostering the birth of Life (founded in 1936) and other glossy photography-centered publications — and thus whole new markets for photos. He angled to become the court portraitist of the rich, famous, and powerful of this era.

His breakthrough was his 1941 photo of Winston Churchill as a great, grand, stately ruler. Churchill's head is spotlit while the rest falls into shadow; the result highlights a defiant expression that was read as his steadfastness during wartime. But what stands out in Karsh's oft-told account is his fawning before Churchill, who was grumpy about posing because his staff had not informed him of the sitting. Karsh wrote, "I timorously stepped forward and said, 'Sir, I hope I will be fortunate enough to make a portrait worthy of this historic occasion.' " Churchill granted him just two exposures. The British leader's expression seems to have been provoked by Karsh's politely plucking his cigar from his mouth.

Which is a reminder that these are expertly posed and lit photos — and that posing and lighting are central to their drama. (By comparison, Arnold Newman stressed geometric composition and Richard Avedon the stark, isolated, high-resolution figure in front of a white backdrop.) Karsh's moment was the '40s and '50s, when he identified, channeled, and manufactured glamour during WW2 and its cold aftermath. He seems to place his subjects on pedestals, which in turn are placed atop mountains, and then he cues sunlight to blaze down on them from billowing clouds. Plus the tones of his black-and-white prints tend to a burnished bronze and velvety blackness that recall the statues of "great men" that occupy city squares. Who wouldn't want to be immortalized by him?

Topics

Topics:

Museum And Gallery

, Fidel Castro, Boston University, Walker Evans, More  , Fidel Castro, Boston University, Walker Evans, Sharon Harper, Sharon Harper, Sharon Harper, Alberto Giacometti, Anita Ekberg, massArt, massArt, Less

, Fidel Castro, Boston University, Walker Evans, Sharon Harper, Sharon Harper, Sharon Harper, Alberto Giacometti, Anita Ekberg, massArt, massArt, Less