FOREFATHER On the occasions when it works, Katz's art often has the intrigue of old snap shows,

interesting because of their colorful glimpses into the past. |

When Alex Katz launched his career as a realist painter in the 1950s, it was a daring move. The big abstract expressionist paintings being made by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and their comrades in New York were the main event then. The formalist critic and abstract expressionist champion Clement Greenberg declared, "Any painter today not working abstractedly is working in a minor mode."

>> SLIDESHOW: "Alex Katz at the MFA" <<

But some, like painter and critic Fairfield Porter, took Greenberg's proclamations as a challenge ("I thought, if that's what he says, I think I will do just exactly what he says I can't do") and returned to realism — including Porter, Katz, Jane Freilicher, Philip Pearlstein, and Larry Rivers in New York; David Park and Richard Diebenkorn in San Francisco; and Lucian Freud in the UK.

Katz — the focus of "Alex Katz Prints," a career-spanning survey of more than 100 works organized by Austria's Albertina Graphic Collection and now at the Museum of Fine Arts (465 Huntington Avenue, Boston, through July 29) — sought to merge the excitement of directly painting landscapes outdoors when he studied at Skowhegan School of Art in Maine in 1949 with the scale and verve of Abstract Expressionism.

The earliest print here is Luna Park, a 1965 screenprint which — like the majority of his prints — copies a previous painting, in this case a 1960 oil of a full moon over a placid Maine lake viewed between a pair of trees. The screenprint cleans up the painting's gestural brushstrokes and distills the composition into clean, flat planes. In the painting, Katz seemed to be muddling his way along as he painted the tree trunks. In the print, they become two sure, sturdy verticals.

|

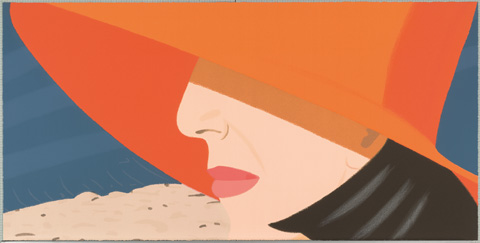

As such, the prints may be the sharpest expression of Katz's style — a focus on surface and fashion and graphic punch. His 1990 screenprint Orange Hat, a glamorous portrait of his wife, Ada, in profile under a wide-brimmed sunhat, resembles a 1930s Art Deco advertisement. The prints' simplified palettes and less expressive brushwork achieve a crisper, sleeker graphic look — and may have encouraged Katz to adopt this style in his paintings of the mid-'60s. "I paint almost like a printer," Katz says in the catalogue, "preconceived, in layers, color into color."

Still, Katz is a middling talent. His subjects are the landscapes around his vacation home in Lincolnville, Maine, and comfortable white New Yorkers from the art, dance, and poetry scenes. He isn't interested in personality or psychology or anecdote, so he often makes all these wildly creative people look vapid. "I like the style to be the content," he said in a 2003-04 interview with curator Robert Storr. But he's poor at style as well. He struggles at anatomy; his renderings are wooden, but his compositions are not stylized enough to get away with it.