|

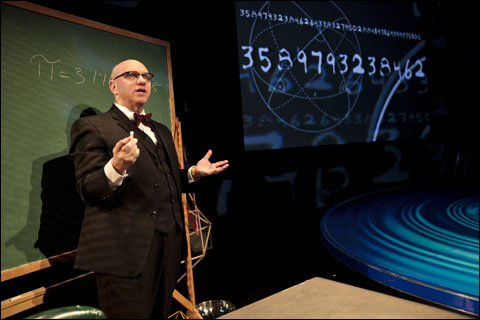

| R. BUCKMINSTER FULLER Thomas Derrah's Bucky is a delighted dervish of thought, his ideas, recollections, prognostications, and tender feelings tumbling like gymnastics in a circus of discovery. |

In 1975 in Philadelphia, R. Buckminster Fuller delivered a 42-hour talk titled "Everything I Know." Even in this day of marathon theater events, that might be a hard sell. As luck would have it, writer and director D.W. Jacobs has distilled the words, wisdom, and biography of inventor, architect, environmentalist, and Renaissance-man-ahead-of-his-Renaissance Fuller into the two surprisingly accessible and entertaining hours that make up R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe (presented by the American Repertory Theater at the Loeb Drama Center through February 5). And ace actor Thomas Derrah, abetted by a few tinker-toy props, some quirky and majestic projections, and a sound design that ranges from music of the spheres to a spot of song and dance, gives a spry and spiritual performance that captures not only the intellectual inventiveness of this iconoclastic thinker but also his childlike enthusiasm. Entering down an aisle, hands tucked into the pockets of a well-worn three-piece suit, Derrah's bow-tied Fuller takes the stage at an elderly gait. But galvanized by an hour or so of his own free-ranging cogitation, he exclaims, "I feel 20 years old again!" Indeed, the self-dubbed Bucky is both Pied Piper of Design Science and his own youthful following — and we the audience, albeit counseled to march to our own drums, are absolutely in the sway of his flute.

Fuller is best known for inventing the geodesic dome and coining the phrase "Spaceship Earth" long before Epcot got hold of the franchise. Yet as the rambling prose poem that is R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe makes clear, that wasn't the half of it. Bucky's brilliance had manifested itself by kindergarten, which found him fashioning tetrahedrons from sticks and peas. But then, as he opines, "Every child is born a genius and is simply degeniused at an early age." Indeed, one of few things about which Bucky is unenthusiastic is formal education: he was thrown out of Harvard twice before packing up his mind and taking it to more expansive places.

Here, in an eclectic brainstorm culled by Jacobs from his life, work, and writings, he riffs with passionate pugnacity about everything from pattern integrity in Nature to having dinner with Albert Einstein. Having resisted suicide in order to devote his noggin to Humanity, sustainability pioneer Fuller fervently counsels using technology to do more with less. And he predicts for the planet either Utopia or Oblivion, admitting that it's "touch and go."

If you think all this sounds heady or boring, think again. "You and I," Bucky tells us early on, "seem to be verbs." And Derrah makes that a mantra. Darting about designer David Lee Cuthbert's blue sphere of a stage, the synergistic center of a swirl of magisterially offbeat projections by video designer Jim Findlay, his Fuller is a delighted dervish of thought, his ideas, recollections, prognostications, and tender feelings tumbling like gymnasts in a circus of discovery.