“Great Ball at the Court of France,” which Ensemble Doulce Mémoire presented at the First Congregational Church in Cambridge last Friday, under the auspices of the Boston Early Music Festival, was a reminder that classical music used to be all about two popular forms, song and dance. The setting was the arrival of Maria de’ Medici from Florence to marry Henri IV king of France in 1600, about the same time that a great ball made it possible for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet to meet. Song gave voice to one’s romantic yearnings; dance was one of the few arenas where those yearnings could be addressed.

“Great Ball at the Court of France,” which Ensemble Doulce Mémoire presented at the First Congregational Church in Cambridge last Friday, under the auspices of the Boston Early Music Festival, was a reminder that classical music used to be all about two popular forms, song and dance. The setting was the arrival of Maria de’ Medici from Florence to marry Henri IV king of France in 1600, about the same time that a great ball made it possible for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet to meet. Song gave voice to one’s romantic yearnings; dance was one of the few arenas where those yearnings could be addressed.

The BEMF program note reminded us that Maria brought with her “commedia dell’arte troupes, dance masters, singers, and musicians of her family’s court.” Doulce Mémoire’s touring “Great Ball” was a more modest affair, with four reed players (headed by company director Denis Raisin Dadre) on dulcians, shawms, and recorders, a lute/guitar player, a percussionist, a singer, and a pair of dancers performing mostly Michael Praetorius and Pierre Guédron before intermission and a variety of 16th-century Italian composers after. Only the dancers sported festive period attire, Marco Bendoni in shirt and hose and then doublet and hose with matching burgundy cap, Bruna Gondoni in a cherry ball gown; the musicians wore unobtrusive shirts and vests and Véronique Bourin a distracting modern black cocktail dress. Bourin’s attractively reedy soprano got lost in the expanse of the church, and she overdid the winks and sly looks in trying to do with her face what she couldn’t with her voice.

There was some fetching byplay between the dancers, but Bendoni wants a more erect carriage and Gondoni a less severe mien, and the pew seating made it difficult to see their feet except when Bendoni was cutting labored capers during the galliard. The traveling version of Jordi Savall’s Hespèrion XXI & La Capella Reial de Catalunya, with greater variety in instrumentation and material, created a more raucous and festive evening when the BEMF brought it to Boston last month.

Still, Ensemble Doulce Mémoire got the point across that Renaissance music is modern, not musty. The (carelessly translated) lyric sheet attested that songwriting hasn’t changed much in 400 years. A maid goes to bed with a passing gentleman; the frustrated narrator laments, “He was not up to the task/As he so clearly showed/Why was I not there?” And the racket produced by the lower-register reeds proved that you don’t have to plug in to get fuzztone.

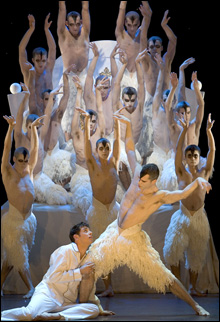

One modern composer who had the measure of dance was Tchaikovsky, in his ballets, of course, but also in his symphonic music, which has been plundered by choreographers as diverse as George Balanchine, John Cranko, and Boris Eifman. His Symphony No. 5 survived Eifman’s Tchaikovsky and his Nutcracker Mark Morris’s The Hard Nut, so no surprise that Swan Lake comfortably accommodates the Matthew Bourne reimagining, in which all the swans are male. It’s not such a stretch — in the traditional Swan Lake, Prince Siegfried wants something other than the arranged marriage with a princess bride to which his royal position has fated him. Substitute gay male for swan and it’s the same story. Bourne could have hewn even closer to the original by changing Prince Siegfried into Princess Brünnhilde and keeping all the swans female.