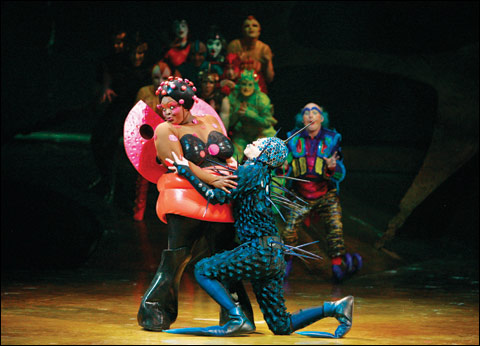

OVO: The stars of Cirque du Soleil’s latest are Michelle Matlock as a plus-size ladybug and François-Guillaume Leblanc as an excitable fly. |

Poetry and dance have some common traits. Both use rhythm, tempo, space, and memory to shape meaning, and both can invoke fast-disappearing images with the most concrete of tools: the verbal lexicon and the moving body. Summer Stages Dance and the Institute for Contemporary Art afforded poet Anne Carson and choreographer/dancer Rashaun Mitchell a Co-Lab creative residency that culminated in an ICA performance on July 20. The two artists were an intriguing match, but the terms of their collaboration seemed more about co-existence than about overlap.

In Bracko, which was created a couple of years ago, and a new work-in-progress, Nox, Carson, Mitchell, and their confederates inhabited the space more or less independently. At moments, her words and his dance collided briefly and glanced off again, but the curious effect was that they were having the same conversation anyway. I couldn't say exactly what that was, but I liked the ambiguity and the sparseness of it. Carson translated the few fragments that are all we have of the Greek poet Sappho and arranged selections for a four-person speaking chorus. Bracko's title refers to the gaps in the ancient manuscripts; these were marked by one speaker's arrhythmic chanting of "Bracket. Bracket. S Bracket." between the lines.

Mitchell and fellow Merce Cunningham dancer Marcie Munnerlyn moved quietly through the space, often holding hands, using lengths of rope to lay out trajectories, perhaps, or define the area more concisely. Throughout the dance, the two window walls of the ICA's Barbara Lee Theater were left open to the expanse of blue harbor and sky. At the end, as Mitchell sat on the floor throwing a length of rope out and pulling it back, a launch motored in as if looking for its berth, skirted the lagoon, and cruised out again. I wondered whether that was part of the choreography.

During a pause, the motorized glare-resistant screens I didn't know were there glided up, and the harbor emerged even more sharply through the windows. A man ran across the outside deck. He gestured, ran, collapsed, and was uncannily suspended in mid fall by the glass. Another man appeared, chasing him, but the bright harborscape made them both appear in silhouette, and soon you realized the second man was inside the windows. These illusions served as a kind of prologue to Nox. The two men struggled, both of them inside now, and ran between the windows and some support columns. The shades came down. For the first time, the theater went dark.

Nox was a meditation on Carson's brother, who ran away in 1978 and died years later in Copenhagen under a new name, having been long out of contact with his sister. I experienced her reading in drifts of melodious speech that only sometimes piled up into meaning. Something about "the strangest thing humans do . . . is history," and how a writer tries to "show the truth by allowing it to be seen in hiding." Thoughts on disappearance, estrangement, death, and how we try to articulate the past.