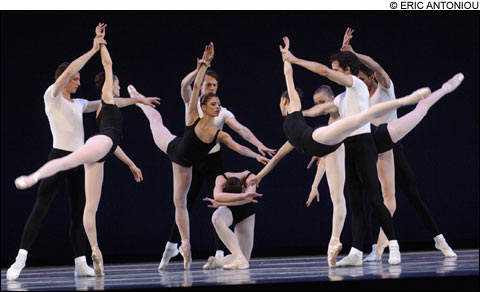

THE FOUR TEMPERAMENTS Kathleen Breen Combes (kneeling) brought off Choleric’s fast and eccentric steps. |

There’s never been a more brilliant exemplar of the ballet art than George Balanchine. In tackling three tremendous works by the 20th-century master, Boston Ballet is giving us a chance to savor these dances again on a living stage. Since Balanchine’s death, in 1983, his ballets are being offered less and less frequently, even by his home company, New York City Ballet. It’s become fashionable in some quarters to worry that his massive genius exerts too much influence on ballet æsthetics. If that’s so, perhaps it’s because no bigger genius has arisen to supplant him in the past 25 years. There’s a reason we still listen to Mozart and Beethoven, folks.

What’s on view at the Opera House through this weekend is dancing at its most demanding and imaginative. I don’t think I’ve ever seen The Four Temperaments (1946), Apollo (1928), and Theme and Variations (1947) together in one evening before. Singly, they pop up now and then, but seen in tandem, they deliver new discoveries about Balanchine and the dancers who embrace him.

Over his long, prolific career, Balanchine evoked many styles and moods. This program does show the neo-classicism of his Ballets Russes period (Apollo), an early example of his American modernism (Four T’s), and his wholehearted celebration of his roots in the Imperial Russian ballet (Theme and Variations). But, different as these three works are, seeing them together, you can recognize certain similarities — families of steps used and usages abandoned, touchstone compositional devices, attitudes to music, and ideas about how to present dancers, how to compose a ballet.

Four Temperaments is based on Paul Hindemith’s Theme with Four Variations, for string orchestra and piano, a piece Balanchine commissioned from the expatriate German composer. Hindemith wasn’t as daring as Stravinsky, but his music had a structural integrity that suited the choreographer wonderfully well. This score, and the ballet Balanchine made to it, is a marvelous exposition of three interrelated themes that begin very simply, sprout into diverse but linked designs, and come together in a grand formal conclusion.

Imagine the shock in 1946 when the curtain went up to reveal a man and a woman, just standing center stage, close together facing the audience, their arms twined in skater’s position, their legs in parallel. They extend their legs one at a time, flex, point, turn, gesture, pivot. But next, instead of being bolstered by other dancers, they leave, and two more couples appear one after the other, to demonstrate some of ballet’s other secrets — allegro, adagio — and some of Balanchine’s own — tilted supported swings, angular lifts, syncopated meters. And this is just the introduction.

I’ve written reams about Four Temperaments, and I could write more here, but space allows only a few remarks about the first two Boston Ballet performances last week. Each of the four sections (the four mediæval humors) features a soloist or solo couple and a small corps of women. None of the title temperaments is literally acted out. In the last movement, they gradually assemble till they make up a full ballet ensemble of 22: 14 corps women, the three introductory couples, and the five soloists.