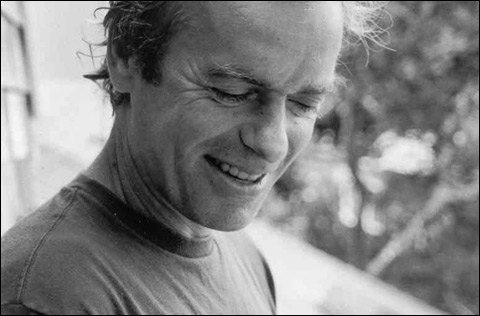

MIRROR MAN: Will Keith shag Scheherazade? Don’t ask. |

| The Pregnant Widow | By Martin Amis | Knopf | 384 pages | $26.95 |

As Under-Secretary of the Ted Hughes Rough Riders (Boston Chapter), I have been delighted by two recent developments. The first of these was the 2009 release of the Eagle Twin album The Unkindness of Crows (Southern Lord), which grafts the vibe (and some of the verses) of Hughes’s nihilist bardic freakout Crow onto slabs of top-notch doom rock. The second was this statement from Martin Amis, in the “Acknowledgements” section of his new novel: “First I offer my enraptured thanks to the memory of Ted Hughes. His Tales from Ovid is one of the most thrilling books I have ever read. My debt to it goes well beyond the exquisite ‘Echo and Narcissus,’ which I quote from and paraphrase throughout.”“Enraptured thanks”: very good. Here’s the thing, though. Although I understand exactly what Eagle Twin are doing with Hughes, Amis has me perplexed. Growling “In the beginning was scrrrrrrr-eeeeeaaam . . . ” over a Mariana Trench of a bass line while the drummer passes out from the pressure — that’s a solid æsthetic venture. The application of “Echo and Narcissus” to Amis’s interior (very interior) history of the Sexual Revolution, however, remains obscure. He keeps jamming it in there, the imagery of duplication and mirroring — “Here in the castle, when you walked down the length of its stone passages, the echo was louder than the footfall. . . . Hello. Echo. And you kept seeing your reflection, too, in unexpected places . . . ” — but I’m buggered if I can quite see why. My fault, I’m sure, but somewhere in the 384 pages of The Pregnant Widow he lost me.

The novel begins hazily, “in a castle on a mountainside above a village in Campania, in Italy.” Clear skies, summer breezes with a waft of inner thigh. The year is 1970. Young Keith Nearing, his girlfriend Lily, and the beautiful Scheherazade (yes, that’s her name) are flopping about, swimming and smoking and sunbathing, accomplices in pleasure. But there are clouds upon the horizon. Clouds in the shape of breasts. In the shape of Scheherazade’s breasts, to be precise, which are troublingly magnificent. The agonies begin. “So you understand about Scheherazade’s breasts,” says Keith to a visitor called Whittaker. “I like to think so,” answers Whittaker (who is gay). “I paint, after all. And it’s not the size, is it. It’s almost despite the size. On that wandlike frame.” “Yeah,” agrees Keith. “Precisely so.”

Will Keith shag Scheherazade? This becomes the matter of the novel, for many pages. Other stuff is going on too, of course. There are grim flashes-forward to Keith in late middle age, in London, cowering before the bathroom mirror (an anti-Narcissus, I suppose). And higher-journalism thoughts upon the Great Changes wrought by the ’60s: “point three in the revolutionary manifesto . . . was this: Surface will start tending to supersede essence. As the self becomes postmodern, how things look will become at least as important as how things are.” (Another gleam of Narcissine reflection as the superficial, the surface, rises toward us.) But in terms of your actual experience, dear reader, this is all so much foreplay. What you want to know is: Will Keith shag Scheherazade?