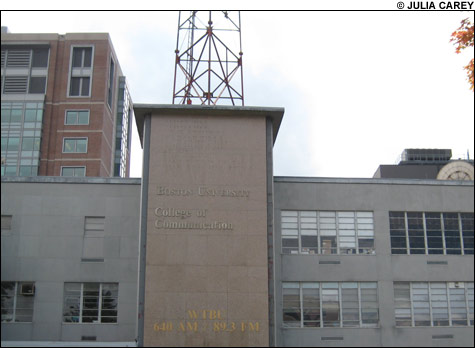

Boston University's College of Communication |

On the face of it, this isn’t a great time to study journalism. Consider, for example, the ongoing bloodletting in American newspapers: earlier this month, Mark Potts, the author of the Recovering Journalist blog, reported that a whopping 6300 employees at the 100 biggest American newspapers had lost their jobs — either by layoff or buyout — in the past year. Granted, the status quo is bleaker in newspapers than in radio or TV. But with the Web cannibalizing those forms of media, too — as well as rendering the old notions of national and regional readerships, viewerships, and listenerships obsolete — the future looks ominously uncertain everywhere in the news business.And yet, counterintuitively, the schools charged with training the next generation of journalists keep pumping out graduates. In 2007, for example, nearly 50,000 students received bachelor’s degrees in journalism and mass communication, according to the 2007 Annual Survey of Journalism & Mass Communication Graduates, which was conducted by the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. Meanwhile, the number of master’s students was close to 3800. (By way of comparison, the 2003 numbers were approximately 46,000 and 4100, respectively.)

True, they didn’t all want to be journalists: the 2007 Annual Survey also found that more new bachelor’s recipients sought work in PR or advertising (about 24 percent) than at daily newspapers (about 21 percent) or in broadcasting (also about 21 percent). Still, given the bleak realities of the journalistic marketplace, isn’t this steady output of embryonic journalists a bit irresponsible?

Not necessarily. For starters — and despite the angst that currently pervades newsrooms around the country — the job market for new journalism grads actually isn’t all that bad. According to the 2007 Annual Survey, for example, 71.7 percent of new bachelor’s degree recipients with news/editorial specializations have full-time work. The job market was better before the dot-com boom went bust: in 1999, that number peaked at 80.4 percent. That said, the 2007 employment rate is better than 2003 (63.5), 2004 (68.8), and 2006 (69.9) — and, somewhat surprisingly, 1990, as well (66.1). Employment for new bachelor’s holders who specialized in broadcast specialists is up too: 67.3 percent of them have full-time jobs — the best figure in seven years, and (once again) an improvement over 1990 (63.4).

The salary situation is murkier, but not exactly grim. Again according to the 2007 Annual Survey, average full-time salaries for new bachelor’s recipients working in both TV and radio dropped slightly this past year, to $24,000 and $25,000, respectively (from $24,400 and $27,000). However, the average daily-newspaper salary for new bachelor’s recipients climbed from $27,000 to $28,000 this past year. And in each of these specialties, the overall salary trend over the past several years is clearly upward.

And what of the Web? After all, online content may be the bane of old media, but it’s also the future of news. Here, too, there’s reason for optimism. Web-based training is standard issue in journalism and mass-communications departments these days, and the job figures reflect this. In 2004, the Annual Survey found that 22.6 percent of new bachelor’s recipients were writing and editing online. The 2007 Annual Survey put that number at a whopping 55.6 percent.

All this is good news for anyone who plans to use their journalism degree in a professional capacity. But as several journalism educators who spoke with the Phoenix pointed out, plenty of other students who major in journalism choose it for the same reasons that others major in philosophy or art history or economics. They find the subject reasonably intriguing; they need to pick something; and they think it could pave the way for future plans, whether they’re indirectly (law school?) or directly related.

“Journalism seems to be an increasingly popular [undergraduate] major, and I think that’s for reasons that have to do with it being interesting, not with people expecting to get a job out of it,” says Nicholas Lemann, dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. “They think it’ll be interesting; they think it’ll be fun; they think they’ll get out of school knowing how to gather facts and write. They’re not expecting a full-time job at the New York Times.”

That same dynamic is even operative at Columbia, which graduates roughly 250 master’s-level students each year and enjoys the loftiest reputation of any American J-School. (Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism is one of only three institutions that trains exclusively graduate students, exclusively in journalism; the other two are the University of California, Berkeley and the City University of New York.) According to Lemann, employment rates for Columbia graduates have actually risen during his five years as dean, a trend he attributes to a few factors (greater emphasis on career services; the tendency of news organizations to replace older staffers with younger, cheaper ones; increased training in Web skills and subject areas).