Most of the job-related fears that keep journalists up at night are relatively mundane. We worry about getting scooped, making factual errors, pissing off the occasional source or story subject. But on rare occasions, a more ominous scenario presents itself — namely, the possibility that our reporting could cause actual harm to someone we cover.

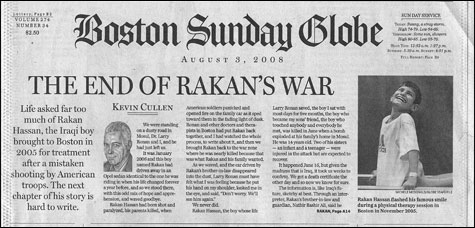

In a grim front-page piece published in the Sunday, August 3, edition of the Boston Globe, columnist Kevin Cullen wrestled with just this concern. Cullen’s subject was the death of Rakan Hassan, a 14-year-old Iraqi boy who was brought to Boston for medical treatment in 2005, after a mistaken attack by US soldiers killed his parents and left him paralyzed.

Cullen had written about Hassan before, in a series of stories that detailed his evacuation from Iraq, recuperation at Massachusetts General and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospitals, and return to his home city of Mosul. Those pieces — published in 2006, before Cullen was tapped as a metro columnist — were models of great feature writing: highly readable, packed with evocative detail, touching but never maudlin.

This story was different. Hassan, Cullen told his readers, had been killed earlier this summer, in a bomb blast at his family’s home. As the story progressed, Cullen explored whether Hassan’s Boston caretakers should have allowed him to return to Iraq — and whether the Globe’s coverage of Hassan’s story might have somehow led to his death.

“All of us who cared about this boy, who loved this boy, are left to wonder: did we do something, however unwittingly, that got him killed?” Cullen wrote. “Did somebody somehow read Rakan’s story, maybe online, and set out to kill him and his family, to prove that anybody who takes sweets or help or anything from the Americans is a collaborator who shall die the death of an infidel?”

After mentioning other potential factors that may have made Hassan a target (his treatment by US Army physicians stationed in Iraq; his brother-in-law’s security job with the Iraqi government), Cullen concluded that the motivations of Hassan’s killers might never be known. But then, a few paragraphs later, he found himself returning to the question: “Would he still be alive if I didn’t write about him? If Michele McDonald’s beautiful photos of him never appeared in this newspaper?”

Who, what, where . . . Why?

Cullen’s anguish is understandable. He spent five months with Hassan. Hassan and his own kids became friends. And, as Cullen noted in an August 4 interview with Robin Young, host of WBUR-FM’s Here and Now, US military officials had cautioned him that his stories might lead someone to target Hassan. (Cullen, who didn’t return a call from the Phoenix, added that these officials couldn’t cite one case in which media coverage of Iraqis had led to retribution, and that Iraqis told him it wasn’t a concern.)

But Cullen shouldn’t fault himself for what he and the Globe produced. Suppose, for the sake of the argument, that Hassan’s killers did see the articles and photos. Let’s imagine that they took umbrage at some of the details included — such as the fact that Hassan’s recovery was bankrolled by Raymond Tye, the Jewish liquor-magnate-cum-philanthropist, or that the US military (including former defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld) played a major role in spiriting Hassan out of Iraq. And suppose, too, that when deciding to target Hassan’s family, they cited these details as justification.

Then try to imagine how this sequence of events could have been avoided, starting with the initial publication of Hassan’s name. Why not keep it out of print?

Problem is, there’s no guarantee that would have been enough. Even if Cullen and his editors had given Hassan an alias, he still could have been sniffed out with a number of other Google-able identifiers: his hometown; his native language (Turkoman); the date and place of the attack that left him crippled (January 18, 2005, and Tal Afar); the fact that his parents died in the attack in question.

And then there are the photos to consider. The original “Rakan’s War” series featured three audio slide shows — with images captured by Globe photographer McDonald — of Hassan in a variety of settings: grinning from a wheelchair; posing for a family portrait in Iraq wearing a Mickey Mouse track suit; crying during physical therapy. McDonald’s photos were perfect complements to Cullen’s prose: each captured the severity of Hassan’s physical trauma and the durability of his spirit. But if Hassan had received an alias, the photos would have had to be eliminated too.

The list of details that could have been omitted to protect Hassan goes on and on. The prominent part played by Tye, Hassan’s Jewish benefactor, could have been nixed. So could the revelation that Hassan’s family received what seems to American eyes the woefully insufficient amount of $7500 compensation — $2500 for each of Hassan’s parents and the car they were driving — after they were mistakenly attacked. That figure isn’t so paltry in Iraq, and could have set up Hassan’s family for blackmail. What’s more, Hassan’s rehabilitation involved extensive work with women, including physical therapist Alison Tate; that could have offended fundamentalist sensibilities.