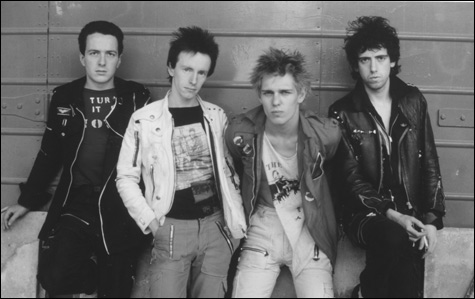

FATED: Strummer (left, with Headon, Simonon, and Jones in the Clash) was a rock star who hated rock stars, an egalitarian punk with a ruthless Machiavellian streak. |

Joe Strummer was the embodiment of punk, up till his final day, December 22, 2002. It was a congenital heart defect that got him — something that could have killed him as a student at Newport College of Art in ’73, or during his squatter years with the 101’ers, the pub-rockers who prepared him for the challenges of the Clash. Instead, he died peacefully, asleep in his comfortable cottage in Broomfield, a tiny farming village nestled in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, 160 miles southwest of London. It could have been tragic: in the years following the end of the Clash, Strummer had entered a deep depression. Except for a few odd jobs (a tour fronting the Pogues; collaborating with Mick Jones on the second Big Audio Dynamite album), he was lost in the wilderness. But by 2002, he was back in top form, having nearly completed his third album with the Mescaleros, the group who brought him back into the spotlight as a frontman, a songwriter, and a punk icon. After the initial shock of his death passed, it felt somehow right, as if his work here were complete and he’d simply moved on.

In fact, for much of his life, as told in Chris Salewicz’s exhaustive new biography Redemption Song: The Ballad of Joe Strummer (Faber and Faber), and in Julien Temple’s new two-hour bio-pic The Future Is Unwritten (opening at the Coolidge Corner this Friday), Strummer seems to have been blessed by the fates. He was given to consulting the I Ching. Paul Buck was one of many friends who were around for John Mellor’s transformation from “Woody” Mellor — a middle-class world-traveled British diplomat’s son — to Joe Strummer. As Buck recounts in Redemption Song, one of Strummer’s big “Should I stay or should I go” dice throws was rigged. It was after he’d been asked to front an as-yet-unnamed punk band with Mick Jones and Paul Simonon. It would mean leaving his friends, the 101’ers. According to Buck, the I Ching advised, “Stay with your friends.” So Strummer “conveniently decided that his ‘friends’ were the Clash,” Buck notes, while wryly observing that it’s “an extraordinarily hippie way to decide to join a punk group.”

There was a certain Machiavellian ruthlessness in that move. Yes, he was deserting a rag-tag crew of squatters. But these people —particularly Tymon Dogg, an unsung folk hero who’d mentored the young Mellor — had fostered the creation of Joe Strummer, the rebel rocker ready to take on the world with his typewriter and his Telecaster. It was a pattern that carried over to the Clash, where in quick order second guitarist Keith Levene was sacked, then original drummer Terry Chimes. Later, Topper Headon, the drummer whose talents (along with Mick’s) propelled punk into uncharted territory, had the misfortune of being sacked just as the Combat Rock song he’d built from the bottom up, “Rock the Casbah,” was breaking worldwide. And, most famously, Strummer and Simonon gave Jones the boot in ’83 — a premature end to one of rock’s great songwriting teams.

Strummer’s seeming cruelty is contrasted, in the film and the book, with the kindness and affection he regularly displayed to friends, fans, and strangers. Redemption Song is peppered with such anecdotes, and it’s a tribute to Strummer’s charisma that even friends he cut himself off from after joining the Clash speak warmly of him in Temple’s film. It’s all part of the walking contradiction Strummer became as the Clash grew. He was a rock star who hated rock stars. Even after the release of London Calling, he was back to breaking into a squat with Dogg. He was compelled to back up words with action, even when it made no practical sense.

For all the energy Strummer put into building his myth, it was still fate that kept him on course. If the 101’ers hadn’t been hitting their stride just as the Sex Pistols arrived, punk could have had its moment without Strummer. But two of the Pistols’ early shows were opening for the 101’ers. All the punks were there, and Strummer was ripe for the picking.

John Mellor was, however, a troubled soul. On his way to Joe Strummerhood, his older brother David had joined the fascist National Front and then taken his own life. The “incident” was rarely discussed, and when Strummer brought it up in a ’77 interview, he got the date wrong — 1971 instead of 1970. But the truth and Joe Strummer were often at odds: the myth didn’t always correspond to the reality, and if this inner conflict drove him creatively, it also fed his dark moods. If not for the support of myriad friends in those years between the Clash and the Mescaleros, the ballad of Joe Strummer might have ended more tragically.