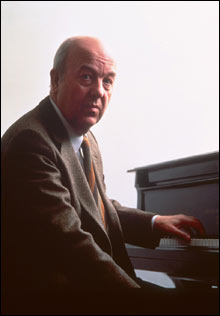

Ivan Moravec |

Now 77, Ivan Moravec has been flying under the classical-music radar for nearly 50 years. A student of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, he made his London debut in 1959 and his American debut with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra in 1964. Starting in 1962, E. Alan Silver’s hip but obscure Connoisseur Society label began releasing recordings. A four-disc Chopin set became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection; the complete Chopin Nocturnes drew a rave review from Harris Goldsmith in High Fidelity; Village Voice jazz critic Nat Hentoff wrote the liner notes for a 1967 Debussy disc, citing Moravec’s command, on previous releases, of “the inner imperatives of Beethoven and Chopin.” A major, and major-label, career seemed in prospect. Forty years later, however, Moravec remains “the elegant, elusive Czech pianist,” as Michael Church calls him in an interview at Andante.com. His repertoire is limited: a good deal of Chopin and Debussy, some Mozart and Beethoven, less Haydn and Schumann and Grieg and Franck and Ravel. He appears infrequently in the world’s great concert halls. Along with the Connoisseur Society, his recordings (some 30 in all) have been released by Supraphon, Vox, Vai, Hänssler, Dorian, and Harmonia Mundi — hardly the who’s who of record labels. Apart from the eight months he spent in England in 1968, he’s lived quietly in Prague with his wife, Zuzana. He never joined the Communist Party, and that must have inhibited his touring. He hasn’t performed in Boston since his 1994 Celebrity Series recital in Jordan Hall, but last Saturday he made his seventh appearance for the PianoForte series at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, just a short hop from Princeton University, where he’s the 2007–2008 Belknap Visitor in the Humanities. He’d be a perfect subject for the New Yorker (not least because of the piano tool kit he carries around with him); maybe Alex Ross will get round to him one of these days.

The hair is a little whiter, but it’s the same chubby, cheerful face (he looks a bit like veteran character actor J. Pat O’Malley) and stocky body, same shy smile, same little-boy walk, bent slightly forward, arms hanging straight down, as if his parents were about to present him to an important visitor. There was, as always, minimal fussing with the piano bench: within five seconds of sitting down, he’d launched himself into Haydn’s Sonata in D Hob. XVI:37. His trademarks — what have made him a cult figure (he doesn’t have a Web site, but his fans do: www.ivanmoravec.net) — are his heroic tone, the big structural arcs he creates, his dance pulse (no thumping on the beat), and phrasing that’s more like breathing. Sitting at the piano, he might remind you of Walter Gieseking. (He’s described Gieseking’s recordings of Schumann’s Kinderszenen and Brahms’s Intermezzi as his “first great experience”; they were mine also.) He’s very still, and his hands move along the keyboard like the spirit of God upon the face of the waters. He says that his tone comes from the weight in his arms, but when you watch him play, it seems to be coming from his very core.

The Haydn sounded a little gentler than the performance on his 2000 Live in Prague disc. It had enough size to be Beethoven, and also wit; it wasn’t dry and it wasn’t overpedaled. The middle-movement Sarabande was by turns operatic and religious, with a firm, clear bass; it left me wishing he’d program Schumann’s Symphonic Études. You could hear the proverbial pin drop in Rogers Auditorium (about 700 seats, mostly filled). Debussy’s Estampes followed, edifices of great tensile strength, with delicate washes of pedal but no blurring. La soirée dans Grenade rocked in its rhythm, as if it were the Habanera from Carmen; Jardins sous la pluie was a driving rain. The audience didn’t so much as hiccup. Then Debussy’s Pour la piano, with its Prélude of Spanish fireworks and harp runs, its Sarabande passing from churchy to bluesy without breaking stride, its Toccata dazzling in its crystal fingerwork and tonal shaping, the music opening like a flower.

The second half of the program was given over to Chopin, four Nocturnes and the F-minor Ballade. The early (despite being Opus 72 No. 1) E-minor Nocturne was vintage Ivan, starting beautifully before taking on ominous weight and inflection, the ornamentation never obscuring the line. The G-minor (Opus 15 No. 3) that followed seemed impatient, searching, and it remained that way even through the chords of its “religioso” second half — quite unlike Moravec’s iconic 1966 recording. The effect was unsettling. Someone actually coughed, and a cellphone went off. (If this had happened in the first half, the audience would have had the miscreant drawn and quartered.) The C-sharp-minor (Opus 27 No. 1), with its stormy distensions, was virile rather than macho, but a sense of haste rather than urgency persisted. The D-flat, Chopin’s “Moonlight Sonata” (and like Beethoven’s, it’s Opus 27 No. 2), rolled with its own ominous waves, and shooting stars in the right hand. The Ballade, Moravec’s signature piece, had a fraction more forward motion than his recordings and, I thought, a fraction less conviction. These were performances of individuality and integrity, but not inevitable the way the Haydn and Debussy had been.