“It’s healing,” counters Madden, “because it’s taking something that would be sitting in a box in someone’s closet or garage, just old clothes taking up space, and making them into something, something you can express yourself onto. And it’s . . . it’s therapeutic, is the word.”

TURNING A PAGE: Proceeds from the sale of Combat Paper goods are going toward a national workshop-and-lecture tour aimed at bringing help to even more vets in need. |

The paper trail

Each workshop begins with an explanation of the papermaking process. The vets then dismantle their outfits and feed the pieces to a beater, which macerates the fiber into paper pulp. The pulp’s pressed into sheets and hung to dry, with stunning results: paper flecked with white (undershirts), threaded with green (fatigues), and streaked with Navy blue.

Since the Combat Paper Project got its start, veterans of wars in Iraq, Vietnam, and Bosnia, and one from World War II, have contributed uniforms to the effort. When a new vet joins, Cameron adds a piece of their uniform to a reserve stock of paper pulp, a bit of which is mixed into each new sheet of paper made. “The project is collaborative in nature,” he says. “We carry the strain in each sheet of paper.”

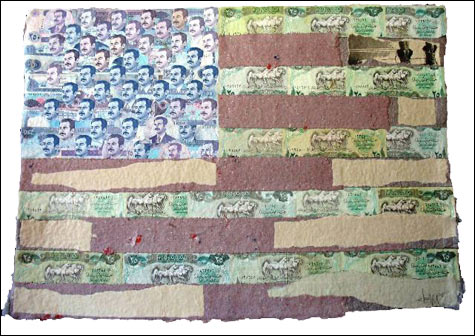

Onto some sheets, the vets screen photographs taken while on duty. They turn other pieces into personal journals or books. The veterans sell their paper through the combatpaper.org Web site and during speaking tours to fund the project. Later this month, Cameron and four other Combat Paper vets will begin a cross-country workshop-and-lecture tour, which will take them from Vermont to the San Francisco Public Library and back. The group will continue the tour in Europe this spring.

The goal is to create an extended community of vets and active-duty troops and reach out to the civilian community. “I would have benefited so greatly when I was overseas if I had known my fellow brothers and sisters in arms were talking about the war back home, were pushing back,” says Cameron. “It would have been completely eye-opening. I wouldn’t have felt so alone.”

“For two years I was making art by myself — I felt alone the whole time,” says Hughes, who is now studying for a master’s degree in Art Theory and Practice at Northwestern University. “It’s inspiring to be with a group of other vets who have had experiences similar to mine. We can find a way to talk about it, to share it.”

“It’s humbling work,” says Cameron during a recent conversation. Since launching the project 17 months ago, he’s seen his art become less angry, less frustrated. “But I don’t think there’s such a thing as letting go,” he says. “You can’t move on. It’s more like moving in. It’s this idea of reconciliation. You’re reclaiming. You’re owning. It’s no longer something you were in service to. Now it’s something you own. It’s yours.”

To find out more about the Combat Paper Project, visit combatpaper.org, or check out iraqpaperscissors.com to view the trailer for a documentary-in-progress on the veterans’ work. Julia Rappaport can be reached at julia.rappaport@gmail.com.