FISH EYES — SIXTH OF TEN BROTHERS Chinatsu Ban’s 2005 sculpture is irresistibly cute.

|

| “Drama and Desire: Japanese Paintings from the Floating World 1690–1850” | Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave, Boston : Through December 16 | “Arts of Japan: The John C. Weber Collection” | MFA: Through January 13 | “Contemporary Outlook: Japan” | MFA: Through February 10 |

Around 1600, after a century of civil wars, Japan settled into an era of relative peace under the samurai warriors of Edo (present-day Tokyo). There and in Osaka and Kyoto, “pleasure quarters” developed. They offered legal brothels, theaters, and teahouses where, the catalogue for the Museum of Fine Arts’ “Drama and Desire” explains, “even the most reliable, serious-minded family man luxuriated shamelessly in all manner of musical entertainment and dance performed by geisha or in witty conversation and other intimacies with a courtesan” — i.e., a prostitute.The contemporaneous prints that captured this “ukiyo,” or “floating world,” are well known, but the MFA’s “Drama and Desire: Japanese Paintings from the Floating World 1690–1850,” in the Torf Gallery, provides a rare sampling of 83 “ukiyo-e” (“pictures of the floating world”) paintings. All are drawn from the MFA’s collection of more than 700, which it proclaims the “finest” and “largest collection of its type in the world.” They were acquired in Japan in the 1870s and 1880s, when Boston and the MFA were visionary in their art collecting. Ah, the good old days.

The highlights include four large, rare, terrific kabuki-theater advertising signboards from the late 1700s that have been attributed to Torii Kiyomitsu or his school. Originally hung at an angle in the eaves of theaters to attract customers, they’re boldly painted and often combine several events from the plays into one scene. One from 1758, said to be the “oldest known extant” kabuki poster, advertises a tale of an unfairly maligned poet, with two trios of actors giving one another the hairy eye along a riverbank. Other posters feature a tea seller haunted by a ghost and a tale of 16th-century warlord seeking revenge on a rival who had assassinated their common overlord.

But mostly the exhibit is girls, girls, girls. Hishikawa Moronobu’s late-17th-century screens Scenes from the Nakamura Kabuki Theater and the Yoshiwara Pleasure Quarter provide a tour of Edo’s “pleasure quarters”: theatrical performances, bordellos, men gawking as prostitutes and their entourages promenade down streets. Throughout the exhibit, ravishingly elegant woman strum samisens, pick flowers, stroll along riverbanks, and just beautifully sit. A woman in a flaming red wig dances with peony branches in her hands in Katsukawa Shunsho’s hanging scroll Shakkyo, theLion Dance (1787-’88). In Utagawa Toyokuni’s large hanging scroll Geisha and Waitress (1804-’18), a woman smiles as she sits reading a love letter and curls her toes (what a lovely detail).

These paintings are often considerably larger than ukiyo-e prints, but the execution remains exquisitely refined. The colors are richer too, but the pictures are still driven by swooping calligraphic linework set against flat areas of pattern and color.

Of the MFA’s 700 ukiyo-e paintings, 100 are sexually explicit “shunga,” or “spring pictures,” which MFA curator Anne Nishimura Morse, who organized the exhibition, says amount to the largest group of erotic ukiyo-e paintings anywhere. (Now that would be an exhibit to see at the MFA.) She sprinkles a few erotic handscrolls throughout the exhibit. They’re filled with couples or threesomes in various states of undress tangled up in explicit sex. The characters’ anatomies kindly swash and squish for the sake of design and clarity. The penises are uniformly hulking.

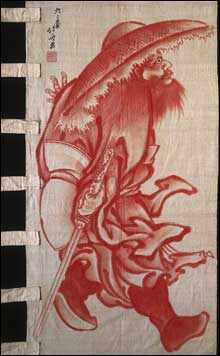

ZHONG KUI, THE DEMON QUELLER:

Hokusai’s painted cotton flag must have been

astonishing when seen flapping in a breeze. |

The exhibit concludes with a gallery of paintings by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). His mastery is apparent. He paints with freedom, energy, precision, and charisma, whether he’s depicting a woman gazing at herself in a mirror, the dazzling feathers of a phoenix, a curling dragon, or an old poet contemplating the great torrent of a waterfall. Zhong Kui, the Demon Queller (1805) depicts a legendary Chinese protective spirit in bold red brushstrokes across a white cotton flag that must have been astonishing when seen flapping in a breeze. The old man strides forward, his big worried eyes sunken into his skeletal face, his robe windswept. His right hand holds his sword precisely; his left reaches up uncertainly.Organized by the Museum of East Asian Art of National Museums in Berlin and presented in the MFA’s Japanese Paintings and Ceramics Galleries, the companion exhibit “Arts of Japan: The John C. Weber Collection” presents, from the New Yorker’s horde, some 80 fine wood, porcelain, and stoneware dishes, screens, scrolls, and kimonos, dating from the 12th to the 20th century. An anonymous 16th-century scroll imagines a 54-round competition among 36 characters from The Tale of Genji. The poets are drawn in fine, uninflected black-ink contour lines as calligraphic text curls about them like smoke or thoughts. Utagawa Toyokuni’s hanging scroll Courtesan in her Boudoir (circa 1818-’25) depicts a pale woman fixing her disheveled hair as her robe falls open revealing her breast. Japanese calligraphy says: “Perhaps you can guess/What has just happened/During a tryst by the pillow!/Asleep, my hair was tangled/By a tempest in the bedroom.”