need to provide and protect. |

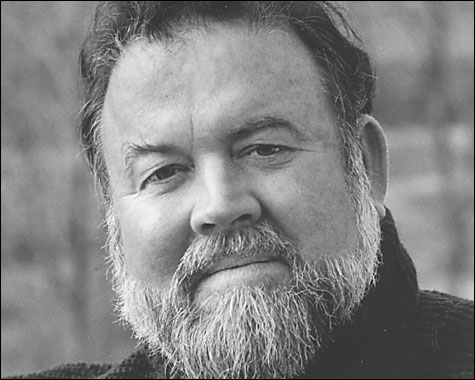

On the train back from New York City late last fall, I held a collection of Andre Dubus’s short stories, a recent gift from a beau. Walking out of a Cambridge bookstore not long before, he had said, “I got you something,” with that mix of pride and nerves that comes with passing along something that you love to someone else, and handed me a copy of Dubus’s Selected Stories. I knew the name — a local guy, Haverhill, it turned out, and the father of novelist Andre Dubus III. But I didn’t know the elder Dubus’s work. So on the train, I started a novella called Rose. And when the violence and emotional heat in that story reached their peak, I put the book on my lap and looked out the window at the passing coast — small bays and crowded harbors and the shadowed backs of old brick buildings, this, around November, when New England’s bones start to show — and I realized my heart was beating faster. The story had quickened my pulse.As I read more Dubus, special-ordering his story collections from his longtime Boston publisher, David R. Godine, I started to feel for the author as I did for another artist, painter Andrew Wyeth. The two have much in common: realists who believe in ghosts, and who, in their art, grapple with mortality, intimacy, the minutiae of domestic life — dishes in the sink, geraniums on the window sill. Their work is somber but not joyless, sad but not maudlin, controlled but never dispassionate.

But it’s how they portray women that attracts me most. With his Helga portraits, Wyeth captures quiet, loneliness, defiance, confidence, connection. Dubus, even more so, has a way with women. He writes them in a manner that suggests a profound respect, especially for those characters who can only be described as housewives. He is never condescending, and always attuned to their specific complexities and pain. It was Anton Chekhov “who showed me that a woman’s soul has a struggle all its own, neither more nor less serious than a man’s, but different,” Dubus wrote in an essay, “Of Robin Hood and Womanhood,” in 1977. And his women do struggle (though that doesn’t sway me from wanting to be one of them).

“I became so sympathetic to the sounds of pain from the female soul that I went through androgynous periods,” Dubus wrote in ’77. That ability to exist in a character’s head — in their sex — shows. It shows in Edith, from the novellas Adultery and We Don’t Live Here Anymore (which together were the basis of a decent film with Peter Krause, Mark Ruffalo, Laura Dern, and Naomi Watts), who tends to her dying lover while her husband cheats with his best pal’s wife. It shows in the story “Miranda Over the Valley,” when the young title character discovers she’s pregnant. And it shows in Finding a Girl in America, when 19-year-old Lori tells her older lover that her friend, the man’s prior love, aborted what would’ve been his child.

Infidelity abounds in Dubus’s work. Doubt in the ability of men and women to sustain lives together suffuses his stories. The tenor of his writing resembles the crushing realism of Richard Yates, a teacher of Dubus’s at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. (The two often shared drinks at the Crossroads, a bar and restaurant at the corner of Mass Ave and Beacon Street.) But unlike Yates — who was equally admired as short story writer and novelist — Dubus stuck with shorter forms: “I love short stories because I believe they are the way we live,” he wrote in 1977. The disintegration of love gets frequent treatment, sometimes slow, sometimes abrupt and violent, always sad. Dubus himself was married three times. But despite all the women and his affinity for them (inside his stories and out), his writing is not feminine. There’s a muscle to it, a physicality, and a need, spoken or not, presents itself: to be a provider, to be a protector.