When in 1976 Jennifer Bartlett premiered her epic painting Rhapsody, John Russell, the chief art critic of the New York Times, proclaimed it “the most ambitious single work of art that has come my way since I started to live in New York,” a work that enlarges “our notions of time, and of memory, and of change, and of painting itself.” It was an astonishing rave that catapulted Bartlett, then in her mid 30s, to the top rank of artists. Thirty years later, curator Allison Kemmerer has assembled 27 works in “Jennifer Bartlett: Early Plate Work,” at the Addison Gallery of American Art, in an effort to trace how the artist arrived at that breakthrough masterpiece.

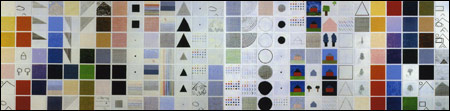

RHAPSODY (DETAIL): “I always had in my mind a painting that was without edges and a painting that was like a conversation or like music.” |

The earliest works here are pencil-and-crayon drawings on graph paper from 1969. In one, Bartlett filled the squares with paired colored dots and then their mixed hues. In another, she selected the color for each square by randomly grabbing crayons from a bowl. It’s all about patterns and chance, self-imposed formulas, theme and variation.

The previous year, she began painting on one-foot square industrially fabricated white steel plates printed with gray grids. She liked their hard surface. They were easily stackable and packable. If you wanted to make the painting bigger, you just added more plates. She filled these grids with arrays of dots that recall a cross stitch or something spit out by a dot-matrix printer.

The regular sequence of dots in one work becomes wave patterns. Four Right Angles (1972) turns a sequence of “L”s into straight lines, “X”s, triangles, radiating stars. In Nine Points (1972), she began with one red dot on the first plate and randomly added another dot to each successive plate, until she ended up with nine dots on the ninth and final plate.

You walk around the Addison trying to decode the formula underlying each set of plates. In Squaring: 2; 4; 16; 256; 65,536 (1973-’74), two dots sit in the top corner of the first plate, four in the corner of the second, 16 in the corner of the third. Two-hundred-fifty-six black dots fill most of the first five rows of the fourth plate. When you multiply 256 x 256, the resulting number of dots fills most of 29 plates. It’s a lesson in the mathematics of population growth.

Such programmatic artworks were all the rage at the time, but they strike me as cold and mechanical, a tedious homework assignment.

Then you walk into Rhapsody. It surrounds you, running 7-1/2 feet high by 153 feet wide, filling a whole room. “I always had in my mind a painting that was without edges and a painting that was like a conversation or like music,” Bartlett tells me when I reach her at her Manhattan studio. “So I decided to use plates. If you have many edges and a space between them, it dissolves the overall edges of the painting. I like the idea of a painting being able to turn corners and go from room to room.”

Rhapsody makes all the other works here seem like rehearsals. Bartlett begins with an overture introducing her themes: three shapes (circle, triangle, square), three sizes (small, medium, large), four kinds of line (horizontal, vertical, diagonal, curved), three ways of painting (dotted, freehand, ruled and measured), four motifs (house, tree, mountain, cloud), 25 colors. “I was just breaking up art for myself.”

She proceeds through numerous permutations. A mountain and cloud rendered in dots, ruled lines, Impressionist dashes. A photo of snow-capped Alps copied, then reduced to lines, shapes, dashes. Planes soaring over a mountain on a moonlit night. A black line wiggling down seven plates pushed together. A simple red house blown up to fill 49 plates. Random colored dots or dashes. Copied photos of houses and trees. Two trees in dashed lines across 49 plates, an imitation of action painting, as if each brushstroke were in quotation marks. Studies of color mixes. It seems to be the whole world — or at least the history of art — distilled to its elements. Your eyes bounce from plate to plate, comparing and contrasting.

Rhapsody climaxes with a cycle of black circles, triangles, and squares in various groupings and sizes that calls to mind Morse code. The coda is a sea of blue and brown rendered in dots or watery dashes. It feels like a camera panning up into the sky or out into the ocean at the end of a movie. You almost expect the word “Fin” to appear.