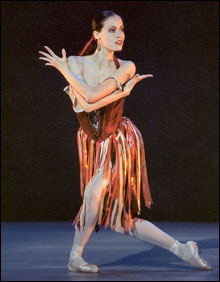

TZIGANE: Natalia Magnicaballi took over one of Farrell’s most celebrated roles without trying to be Farrell. |

In her Pillow Talk at Jacob’s Pillow last weekend, Suzanne Farrell was asked what she expects of the young dancers who are reviving George Balanchine’s ballets under her direction. Farrell said she teaches the steps of the ballets and all the other information she gathered as a principal at the New York City Ballet during Balanchine’s golden age. But then, she said, she wants the dancers to find their own way into the works rather than copy the dancers who came before them. “I rehearse the possibilities, not an opinion.”As represented by the Susanne Farrell Ballet’s programs at the Pillow, Balanchine’s repertory carries the usual problems of recovery and authentication, plus an added burden. We haven’t got the advantage of historical distance. The dancers who created the ballets are still here to teach them; the original performances live on in the audience’s memory or on film. This can be daunting for young recruits.

Balanchine’s ballets are not in need of interpretation according to Farrell: “The steps and how you do them are the character.” But the truth is, great dancers co-create the steps, imprint them with style. I think Balanchine wanted that, no matter how loudly he spoke the gospel of neutrality.

Natalia Magnicaballi took over Tzigane, one of Farrell’s most celebrated roles, without trying to be Farrell. In the process she revealed something Farrell’s own performances overshadowed. Tzigane, to Ravel’s symphonized Gypsy music, is an interesting choreographic progression, not just a flamboyant star opportunity.

It begins with a long violin solo. The ballerina dances and mimes a whole series of melodramatic encounters with an imaginary partner, or perhaps she’s telling fortunes. When the orchestra enters, along with her real partner (Runqiao Du Saturday afternoon), they dance a steamy duet, but he seems to tame her a little. Eight other dancers arrive, and the passion is restrained even more, and whole thing becomes a formal dance — Gypsy steps conventionalized into a classical ballet.

I purposely haven’t looked at Farrell’s performance with Peter Martins (preserved on a Nonesuch DVD of two New York City Ballet programs for Dance in America) but I see it clearly anyway, in memory.

It was Elisabeth Holowchuk, in Clarinade, who conveyed that sexy, mischievous side of Farrell. Clarinade was one of the first things Balanchine made for Farrell, with Anthony Blum, when she was a teenage newcomer to the company in 1964. It was part of a larger Morton Gould ballet d’occasion that inaugurated City Ballet’s tenure in the new New York State Theater at Lincoln Center.

Farrell has retrieved the Contrapuntal Blues pas de deux, minus its additional two couples, from some archival film. Holowchuk, partnered by Benjamin Lester, brings back that jazzy, brazen creature with the extraordinary legs, flexible back, sassy hips, slouchy shoulders, sly glances, and complicity in lifts that were one girlish flip away from debauchery.

These wanton females, adolescent or mature, hardly define all of Suzanne Farrell’s possibilities, any more than Farrell in all her guises could have fully populated Balanchine’s creative universe. She’s smart to have chosen some ballets for her company that aren’t identified with her own performances.

Balanchine used Delibes’s music from Sylvia and La Source several times, first for Maria Tallchief, then for Melissa Hayden, but the indelible La Source for me, and the one reconstructed by Farrell, was done in 1968 with Violette Verdy and John Prinz. Big, plush Shannon Parsley (a former Boston Ballet corps member) had enough of Verdy’s feminine épaulement, her assertive footwork, to suggest the ballet’s French flavor, but no one else I ever saw had Verdy’s ballon and wit.

The Mozart Divertimento No. 15 reached its final form in 1956 headed by an all-star cast of five drastically different ballerinas. Just watching Farrell’s young dancers take on the challenging variations, duets, and lively ensemble work is an education in ballet’s tremendous expressive range, its headiest demands.